Banning 25 Books in J&K: Shielding Minds or Selling Narratives?

The government’s recent ban on “secessionist” literature may have done the opposite of its intent — boosting online searches, reviving forgotten authors and giving critics fresh ammunition.

By:Kanwal Krishan Lidhoo*

They say the quickest way to make someone read a book is to tell them they can’t. Jammu & Kashmir’s recent ban on 25 titles — accused of promoting secessionism and false narratives — might just prove that old truth. Within days of the announcement, online searches for these books shot up, and names most people had never heard of began trending in niche reading circles. The irony? In an age where PDFs, Kindle editions and overseas libraries are just a click away, banning a book might be the most effective way to market it.

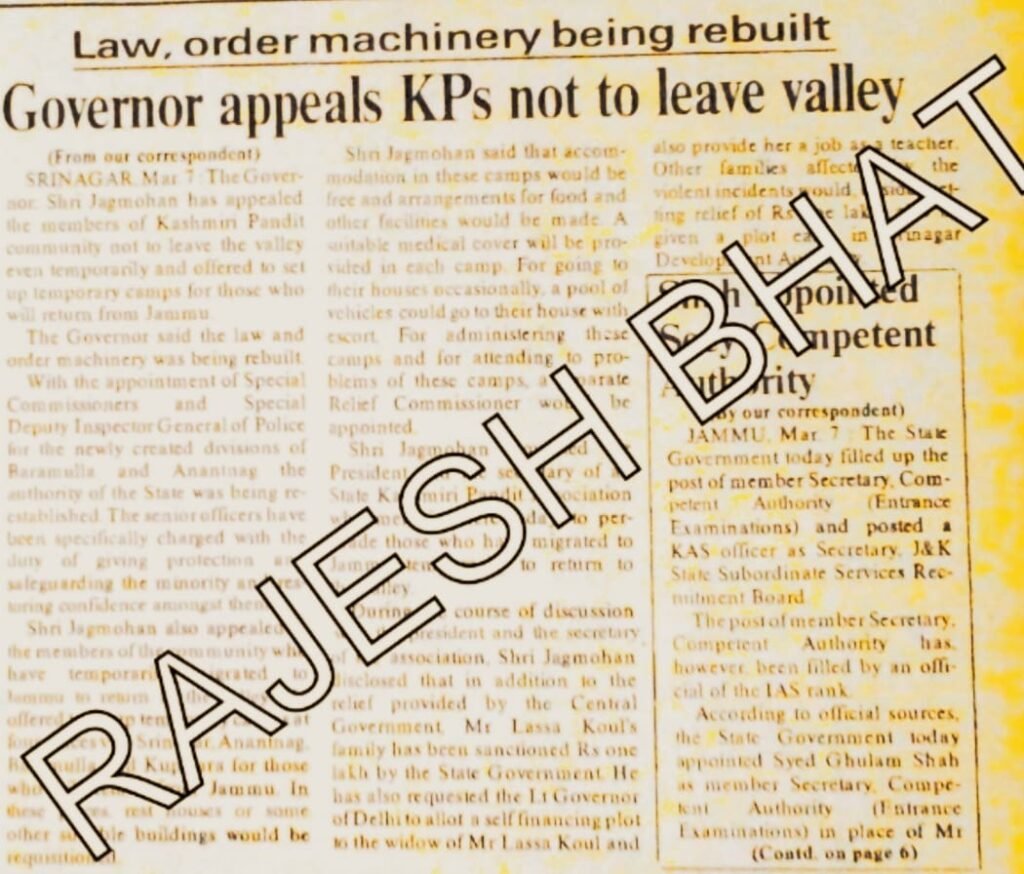

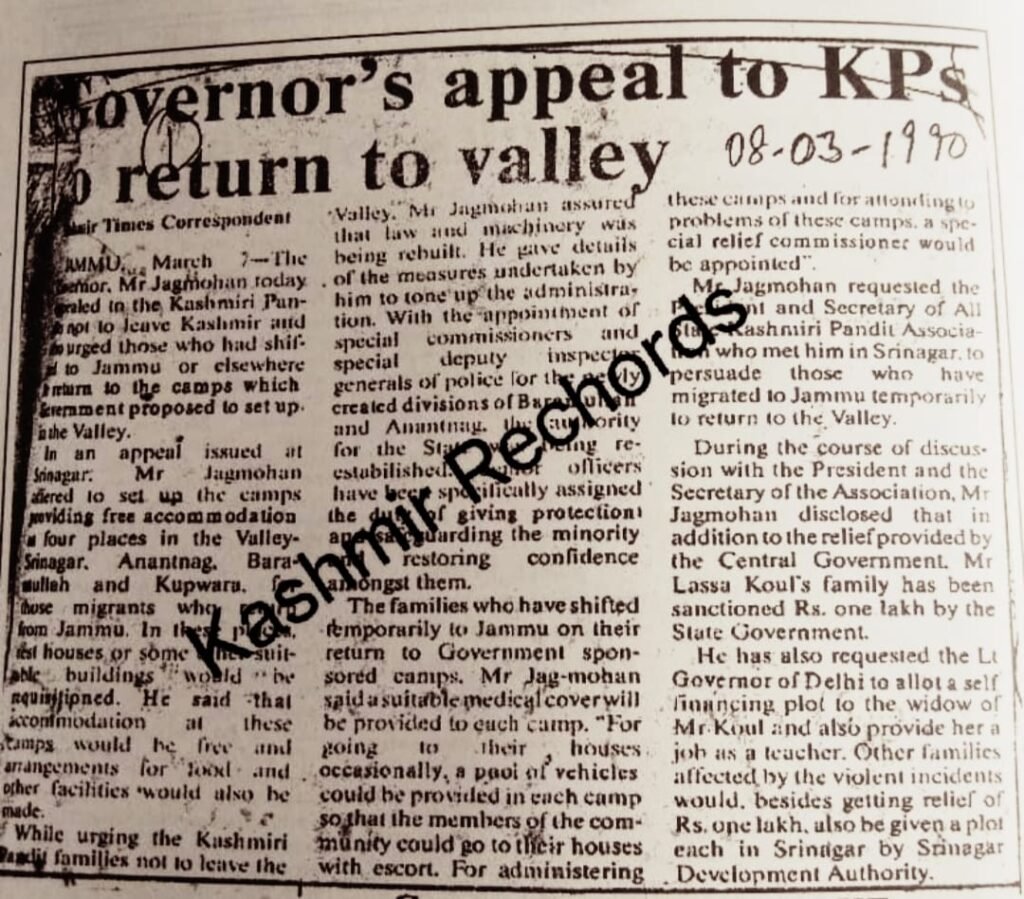

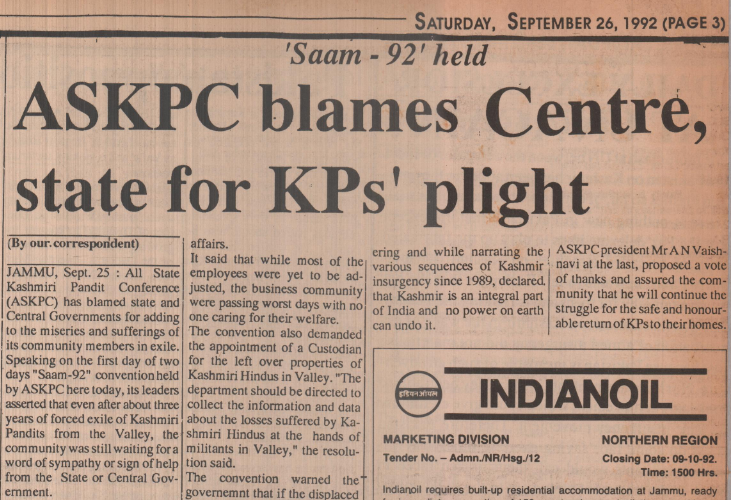

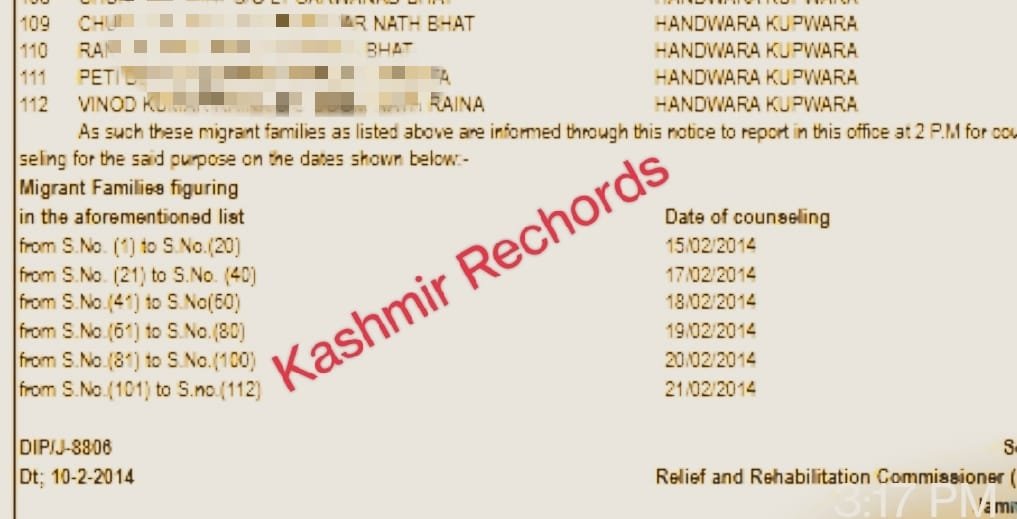

The Jammu & Kashmir Home Department’s move — followed by raids in to seize copies — has triggered a mixed response. The official justification is that these books distort history, glorify terrorists, vilify security forces and promote alienation, thereby influencing youth towards radicalization.

A notification signed by Principal Secretary Chandraker Bharti, on the orders of Lieutenant Governor Manoj Sinha, stated:

“Certain literature propagates false narrative and secessionism… This literature would deeply impact the psyche of youth by promoting a culture of grievance, victimhood and terrorist heroism.”

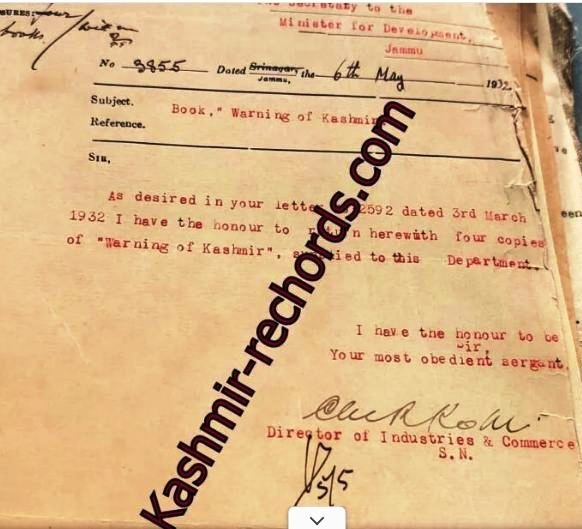

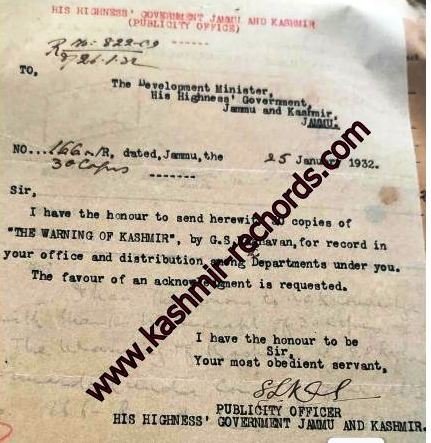

Yet, the timing and practicality of the ban invite questions. Many of the titles have been in circulation for decades. Take Al-Jehad Fil Islam by Syed Abu Ala Maududi — published by Markazi Maktaba Islami, Delhi-6 and available in Kashmir since the 1980s, and some other books even stocked in public libraries through government purchases. If the aim is to prevent exposure, the horse may have bolted long ago.

The ban applies under Sections 152, 196, and 197 of the Bhartiya Nyaya Sanhita 2023, citing threats to India’s sovereignty and integrity. But while J&K shops are now forbidden from selling them, ironically they remain freely available elsewhere in India and online. This creates a paradox — a book inaccessible in Jammu and Kashmir can still be ordered from Delhi or downloaded in minutes.

In fact, the “forbidden fruit” effect seems to be in full swing. People who never knew these books existed now have the titles on their radar. Obscure authors risk being elevated to the status of “free-speech martyrs’’, their works gaining an audience they might never have reached otherwise.

Panun Kashmir leader Shailendra Aima summed up the irony in a Facebook post:

“Writers like Arundhati Roy and A.G. Noorani have long been exposed for their biased takes… Their influence has waned. Their arguments have been countered and discredited in the court of public opinion. So what exactly has the state gained by banning them now, except making them relevant again?”

Critics argue the State could have taken another path — commissioning respected historians and scholars to dismantle the books’ claims point-by-point. J&K has no shortage of credible voices capable of providing fact-based counter-narratives. This approach might have undercut the books’ influence without giving them a publicity boost.

The deeper irony is that anyone truly inclined towards secessionism will have no difficulty finding these works online, often hosted in overseas archives beyond India’s legal reach. The ban, instead of shielding impressionable minds, may simply have served as a promotional campaign for the very narratives it sought to silence.

So, was this a miscalculated move? In the battle of ideas, persuasion often trumps prohibition. And by choosing the latter, the state may have scored a “self-goal” — amplifying voices it hoped to erase.

At Kashmir Rechords, we believe that truth, when told fearlessly, outlives every attempt to bury it.

Combating secessionism is rarely achieved through book bans; it is better served by drawing a broader, more compelling line of comparative viewpoints. Governments and engaged elements of civil society can always counter such narratives with informed, well-reasoned perspectives. This intellectual space, however, must not be extended to terrorist groups or individuals who use online platforms to propagate violence and toxic ideologies. A well-researched book, rich with facts and context, can effortlessly strip away the superficiality and distortions found in works the state seeks to ban.

- *Kanwal Krishan Lidhoo is a noted Broadcaster, Author and acclaimed Translator approved by Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi. He is a Founding Director of Kashmir Rechords Foundation.