(By: K R Ishan)

Kashmiri Pandits have suffered a lot at the hands of tyrants! Even Nature has been cruel towards them!. This is evident from that fact that over 9,000 Kashmiri Pandits, including children and women, had perished on their way to Harmukh Ganga pilgrimage, over 500 years ago in 1516 AD! Harmukh, originally “Haramukuta” is a mountain with a peak elevation of 5,142 metres (16,870 ft), in the present Ganderbal district of Jammu and Kashmir.

There is a mention of this tragic incident in many books and records, but unfortunately, most people are unaware of this catastrophe that had befallen on Kashmiri Pandits!

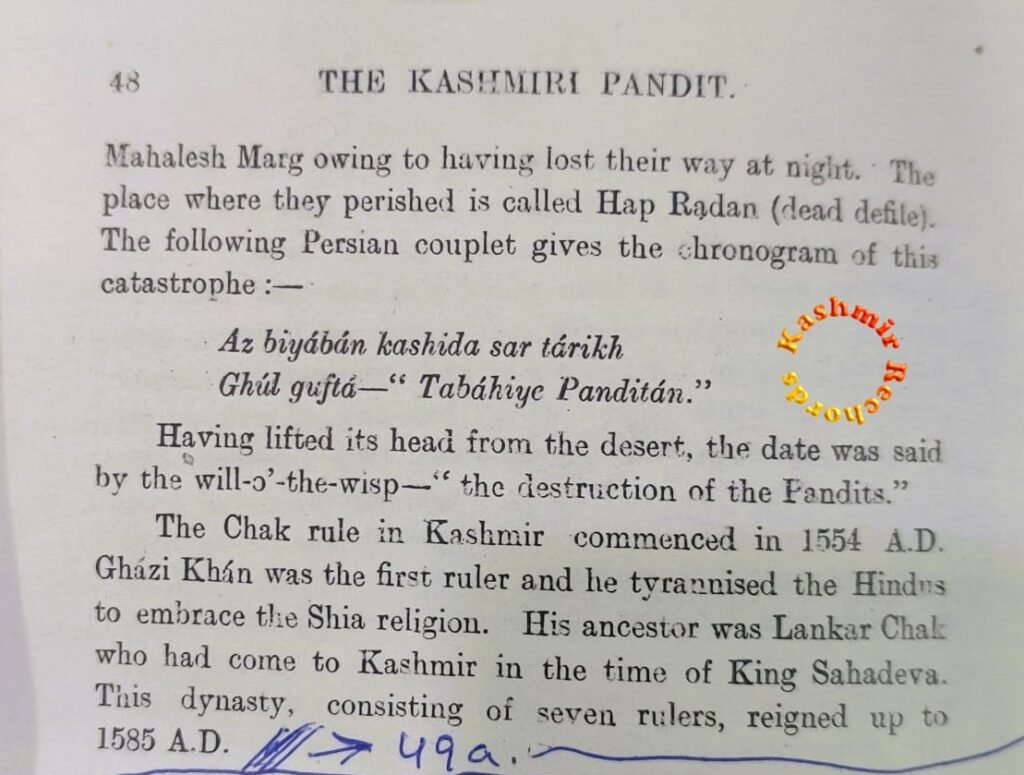

Pandit Anand Koul in his 100 year old book “The Kashmiri Pandit’’ (1924) makes a mention of this tragic incident. The incident had taken place during the reign of Sultan Fateh Shah (1489 A.D.), the 12th Sultan of Kashmir. For nine years, his Minister was Musa Raina, a bigoted Shia, who had tyrannised Hindus, imposing jaziya on them and destroying their temples.

A Double Whammy for Kashmiri Pandits

It is said of Musa Raina that he had forcibly converted 24,000 Brahmin families to his own religion. In 1516 AD, about 10,000 Kashmiri Pandits had decided to undertake a pilgrimage to Harmukh Ganga, in order to immerse the ashes of those 800 Hindus who had been massacred during Ashura. However, Nature too resorted to a double whammy when Pandits on a pilgrimage to the Harmukh Ganga, perished at Mahalesh Marg owing to having lost their way at night. According to Anand Koul, the place where they perished is called Hap Radan (dead defile).

Anand Koul quotes the following Persian couplet that gives the chronogram of this catastrophe:-

Az biyábán kashida sar tarikh Ghút guftá “Tabáhiye Panditán.”

—-Meaning “having lifted its head from the desert, the date was said by the will-o’-the-wisp— “the destruction of the Pandits’’.

Poet-historian Suka Pandit too says about this cataclysm. “Ganga was oppressed with hunger, as it was after a long time that she had devoured bones; she surely devoured the men also who carried the bones.” It was in fact after a gap of so many years that Pandits were allowed to go on a pilgrimage to Harmukh Lake, which, however, ended in the most devastating tragedy. Suka Pandit was a Kashmiri poet and historian who wrote Rajatarangini between 1517 and 1596. A student of Prajyabhatta, the work of Suka Pandit is considered a supplement to Kalhana’s Rajatarangini.

Dr Satish Ganjoo, a noted Historian and a Senior Faculty at Central University of Himachal Pradesh, in his research paper “ A Political Study of Ancient Vedic-Saraswat Kashmiri Pandit Society’’, published in June, 2017, also makes a mention of this natural catastrophe that had befallen Kashmiri Pandits over 500 years ago. However, while Pt Anand Koul mentions 1516 AD (923 Hijra) as the year of tragedy, Dr Ganjoo quoted the year of tragedy as 1519.

The Dreaded Tyrant Soma Chandra ( Musa Raina)

The tragedy at Harmukh Lake had occurred as the Kashmiri Pandits who were allowed to perform this pilgrimage after a long time, wanted to perform the religious rites of all those near and dear ones who had been killed during the era of Mir Shamas-ud-Din Iraqi, the founder of Nurbakhshiyyeh Order (Shia sect) who had visited Kashmir Valley twice in 1477 AD and 1496 AD for propagating his faith. He was helped in his “mission’’ by Soma Chandra, the most dreaded tyrant, who had rechristened himself as Malik Musa Raina after converting to Shia Islam.

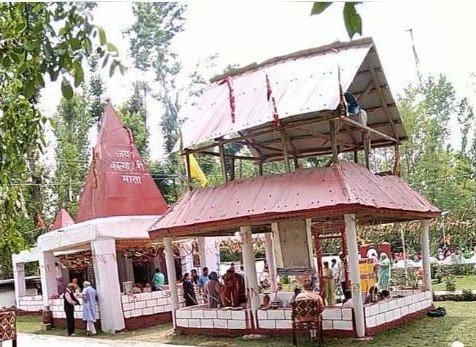

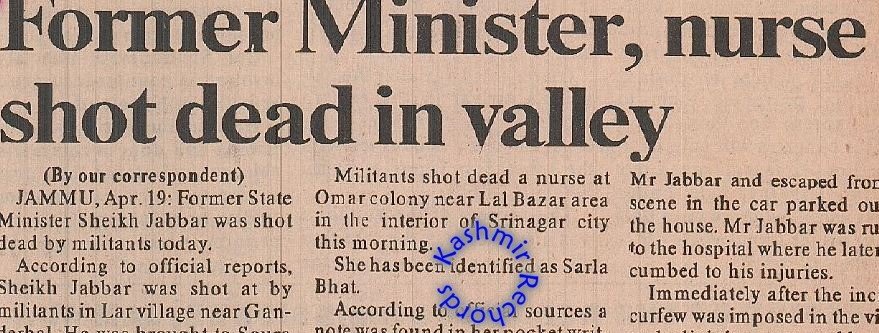

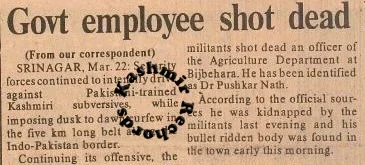

Not only were the vulnerable Brahmans, even the Sunni Muslims also violently converted to Shia sect by murderous techniques. This dogmatic fanaticism had even crippled the Sunni ruler of Kashmir, Fateh Shah (AD 1510-1517). A khanqah was built at Zadibal, Srinagar by Iraqi, which became the nucleus of Shia concentration.

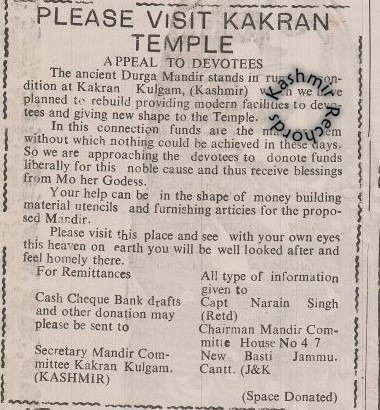

Burning Sacred Threads of Pandits

In his Book, “ This Beautiful India –Jammu and Kashmir” ( 1977), Dr Sukhdev Singh Chib mentions that Iraqi had even issued orders that everyday about 1500 to 2000 Brahmans be brought to his doorsteps, remove their sacred threads, administer Kalima to them, circumcise them and make them eat beef. These decrees were ferociously and brutally carried out. The Hindu religious scriptures from 7th century AD onwards and about 18 magnificent temples were destroyed, property confiscated and women abused. Thousands of Brahmans had killed themselves to evade this horrific barbarism and thousands migrated to other places, resulting in their third tragic mass exodus from the Valley. Those who stayed behind were not only forced to pay jaziya, but their noses and ears were chopped off.

According to Baharistan – i -Shahi, “Dulucha, a Tartar chief from Central Asia, who had invaded Kashmir with 60,000 strong horsemen, had also inflicted terrible miseries upon the people including the Brahmans.

According to W.R. Lawrence, Brahmans of Kashmir were during those days given three choices—death, conversion or exile. “Many fled, many were converted and many were killed, and it is said that this thorough monarch (Sikandar) burnt seven maunds of sacred threads of the murdered Brahmans”. As for the statement of Lawrence, six maunds of sacred threads of converts and seven maunds of murdered Pandits were burnt. The number of people, to whom these thirteen maunds of sacred threads belonged, might have been tremendously colossal. A mammoth number of the Pandits also went into exile, causing the first disastrous mass exodus of the community. Not only Sikandar- the Butshikan, but Suha Bhatta – the convert, also was responsible for this barbarous, murderous and cruel approach towards Kashmiri Pandits.

The brutal religious persecution of the Kashmiri Pandits has been borne testimony to by almost all the Muslim historians. Hassan, Fauq and Nizam–ud–Din have condemned these excesses in unscathing terms. It was the reign of terror and homicide. Even then, they did not forget their past and rich tradition. As the custodians of their extraordinary cultural heritage, they wrote the illuminating treatises on the stupendous Kashmir Shaivism, colossal literature, splendid art, marvellous music, grammar and medicine.