By: Kashmir Rechords Archival Desk

Few people remember that November 7, 1947 marks one of the most decisive days in India’s post-Independence history — the Battle of Shalateng! Fought on the misty outskirts of Srinagar, this fierce engagement between Indian soldiers and tribal raiders supported by Pakistan and her Army, proved to be the turning point in the first Indo-Pakistani War (1947–48).

In just a few hours of intense combat, Indian forces not only saved Srinagar from certain capture but also secured the very accession of Jammu and Kashmir to the Indian Union, signed only a few days before this battle.

The Shadow Before the Storm

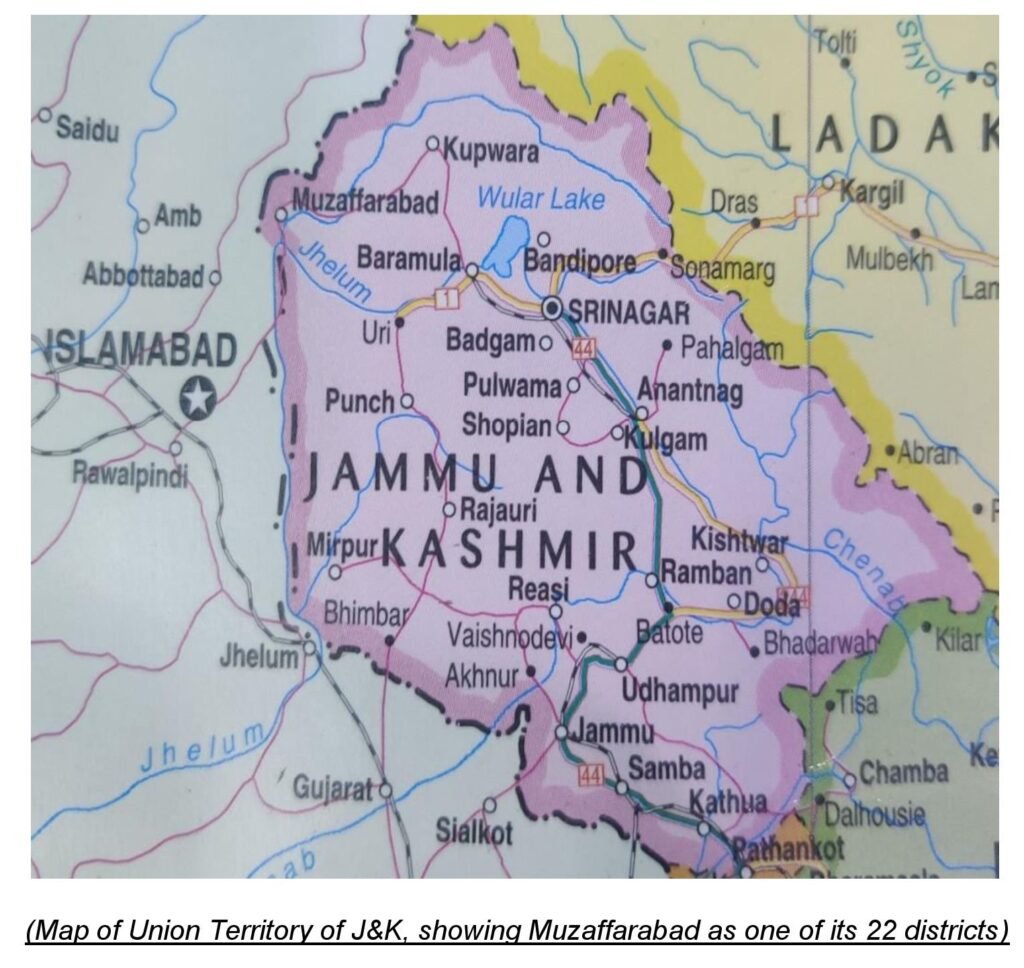

The story began weeks earlier, on October 22, 1947, when thousands of tribal raiders — mainly Pathans from Pakistan’s North-West Frontier Province — swept into Kashmir. With the connivance of Pakistani authorities, they advanced swiftly through Muzaffarabad, Uri and Baramulla, plundering villages, killing civilians, and creating terror in their wake.

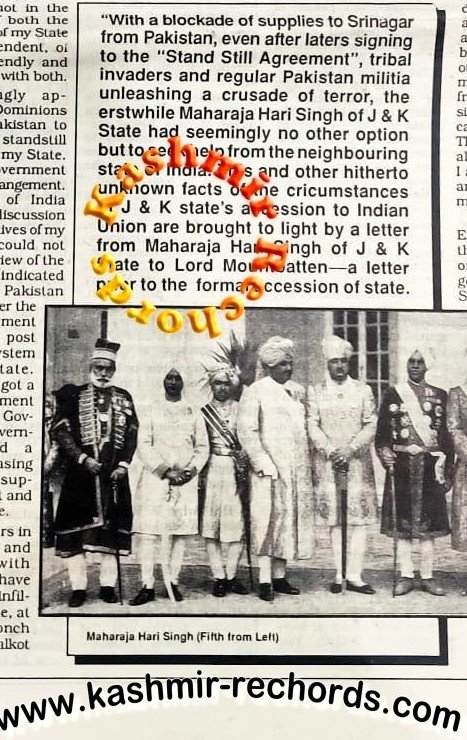

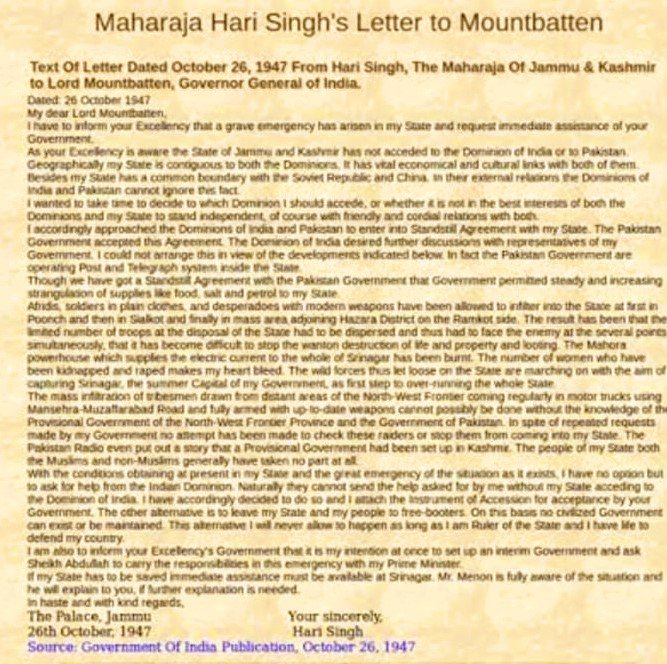

With his forces overwhelmed, Maharaja Hari Singh signed the Instrument of Accession on October 26, 1947, bringing Jammu and Kashmir formally into the Indian Union. Within 24 hours, Indian aircraft began airlifting troops to defend Srinagar, as the enemy closed in.

The first units of 1 Sikh Regiment landed at Srinagar airfield on October 27, 1947, establishing a crucial defensive base. Yet, the enemy remained dangerously close — their next objective was to storm Srinagar itself.

Prelude to Shalateng: The Battle of Budgam

The first major confrontation took place at Budgam on November 3, 1947, where Indian forces halted the tribal advance, safeguarding the Srinagar airfield — the city’s only lifeline for reinforcements and supplies.

Aerial patrols the following days reported alarming news: large enemy concentrations near Shalateng, barely 10 km from Srinagar. It was clear that a decisive clash was imminent — one that would determine the fate of the Valley.

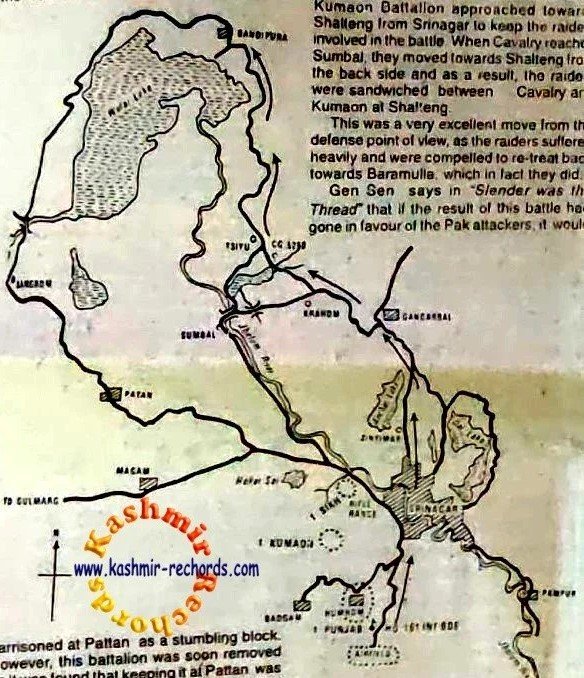

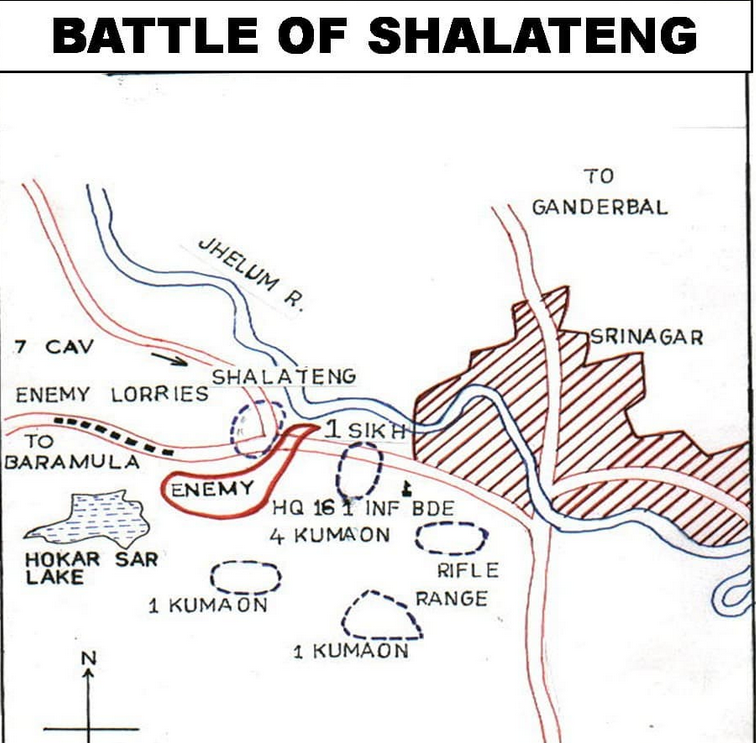

At dawn on November 7, 1947, the Indian Army struck back with precision and resolve. Under the leadership of Lt. Gen. L.P. Sen, commander of the 161 Infantry Brigade, Indian troops launched a meticulously planned Pincer Attack on the enemy.

1 Sikh, 1 Kumaon and 4 Kumaon Regiments spearheaded the frontal assault. Armoured cars of the 7th Light Cavalry, secretly maneuvered through Sumbal via Ganderbal, struck from the rear. Spitfire aircraft of the Royal Indian Air Force (RIAF) strafed enemy positions from the skies, scattering their formations.

Completely taken by surprise, the Pakistani tribal forces — which included regular soldiers in disguise — were trapped between advancing Indian units. What followed was a rout. Over 600 raiders were killed, hundreds fled in panic, abandoning lorries, arms and ammunition on the battlefield.

By nightfall, Indian troops had pushed through to Pattan town. The next morning, they reached Baramulla, and within a week, the entire stretch up to Uri was recaptured. The tide of the war had decisively turned.

“Slender Was the Thread” — The Commander’s Own Words

In his celebrated memoir, “Slender Was the Thread,” Lt. Gen. L.P. Sen recounts the tense, chaotic days when Kashmir’s fate hung by a thread. He notes that the entire counteroffensive at Shalateng lasted barely 20 minutes from the command ‘Go!’ — yet its outcome altered the history of the subcontinent.

The battle also underscored the collaboration between Indian military forces and local Kashmiri support, which was instrumental in the success of this operation. The Battle of Shalateng also remains a powerful symbol of the determination, strategy and sacrifice that defined India’s early years of independence, embodying a legacy of resilience and tactical prowess. He credits Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah‘s National Conference workers for suggesting and guiding the cavalry’s redeployment through Sumbal, a move that proved crucial in outflanking the enemy.

When Srinagar Slept, History Awoke

Curiously, as the battle raged only a few kilometers away, most residents of Srinagar , according to the book remained unaware of the decisive encounter unfolding in their backyard. The city’s calm was deceptive; the outcome of that unseen battle determined whether Srinagar would fall to invaders or stand free. When news of victory reached the city, joy and relief swept across the Valley. For the first time in weeks, Kashmiris dared to hope again. Thus The Battle of Shalateng was not merely a military engagement — it was the moment that saved Kashmir. The triumph secured Srinagar, ensured the safe landing of reinforcements and provided India the breathing space to consolidate its hold over the Valley.

Had the outcome been different, as Gen. L. P Sen himself admitted, “it would have been nearly impossible to save Kashmir.” In his own words “The thread was slender — but it held. And with it, held the fate of Kashmir”

The battle also exposed the direct involvement of Pakistan’s regular troops among the so-called tribal invaders — a fact that shaped the trajectory of the conflict and the politics of the region for decades to come.

While countless battles fought on Indian soil are etched in public memory, the Battle of Shalateng remains a forgotten gem of courage and strategy. It deserves its place alongside India’s greatest military victories — not merely for its tactical brilliance, but for what it meant to the soul of a newly independent nation.