(Kashmir Rechords Exclusive)

It may sound startling now, but history records a moment when the Union Government formally ordered that the migration of Kashmiri Pandits from the Valley be stopped. Even more strikingly, those who had already fled were expected to return to Kashmir—not to resettle elsewhere, but to live inside protected camps within the Valley itself.

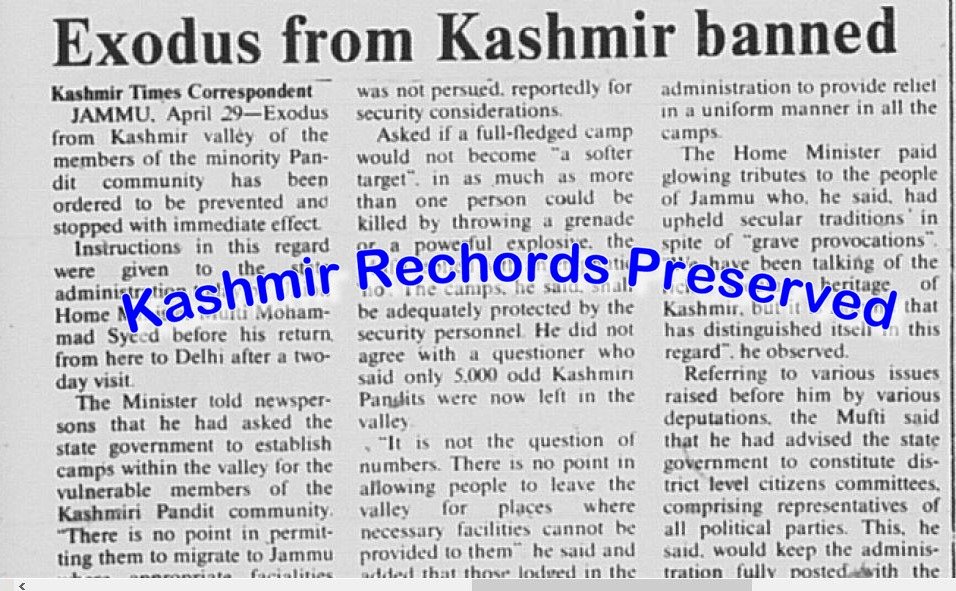

This extraordinary directive came on April 29, 1990, announced by none other than Mufti Mohammad Sayeed, then India’s Union Home Minister, barely a few months after the community’s mass displacement had shaken the Nation.

During his two-day visit to Jammu, Mufti Mohammad Sayeed had instructed the then Jammu and Kashmir administration to prevent any further migration of Kashmiri Pandits with immediate effect. The directive was unambiguous: the exodus from Kashmir had to stop.

Addressing a press conference before returning to Delhi, Mufti had made it clear that the Centre did not favour relocating Pandits to Jammu or elsewhere outside the Valley. Instead, he directed the government to establish secure, well-protected camps within Kashmir for vulnerable members of the community.

“There is no point in permitting them to migrate to Jammu,” the Home Minister said during the press conference, pointing to the lack of adequate facilities there—particularly in the harsh summer months.

Kashmir Rechords, by reproducing the newspaper clipping of April 30, 1990, seeks to preserve this largely forgotten record—not to reopen old wounds, but to document a critical truth: that the Kashmiri Pandit exodus was never officially intended to be permanent, and that at a crucial moment, the Indian State attempted—however imperfectly—to halt it.

Pandits as ‘Soft Targets’—Yet Asked to Stay

Mufti had acknowledged what many already feared: Kashmiri Pandits had become “soft targets” for militant groups, amid a sharp rise in targeted killings. Yet, rather than allowing people to flee, his solution was containment and protection within the Valley.

The idea was like this:

Pandits would be settled in protected zones, guarded by security forces, rather than dispersed outside their homeland.

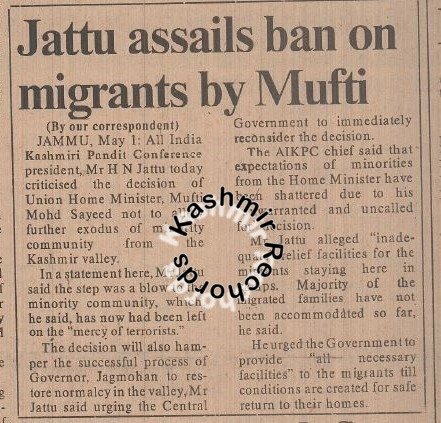

Newspapers of the time prominently quoted the Home Minister lamenting that Pandits lodged in camps in Jammu were living without even basic essentials—“without cots and necessities”—arguing that migration to places unprepared to support them only worsened their suffering. Yet a section of Pandit leadership of that time opposed and assailed Mufti for his order to ban exodus of Pandits from Kashmir.

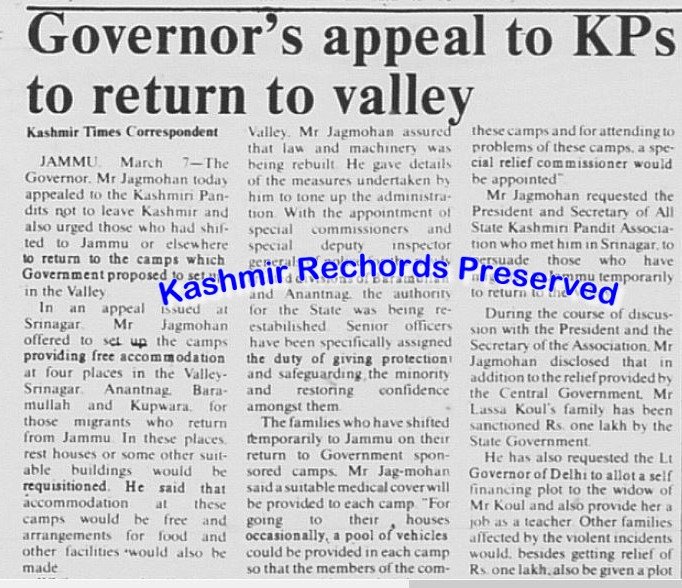

Jagmohan’s Earlier Appeal—and the Community’s Rejection

Mufti’s proposal was not entirely new. Just weeks earlier, on March 7, 1990, then Governor Jagmohan had too publicly floated a similar idea. He had appealed to Kashmiri Pandits not to leave the Valley and urged those who had already fled to return, assuring them full protection in camps to be set up at district headquarters.

That proposal, too, met with strong resistance from the displaced community, which viewed the idea of protected camps inside a hostile environment with deep suspicion and fear. Security concerns, coupled with the trauma of recent killings, led many Pandit leaders to outright reject the plan. Jagmohan’s appeal, however, had came at a time when the community was deeply traumatised. Targeted killings, intimidation and nightly slogans had shattered trust. For many Pandits, the idea of returning to live in camps inside the Valley—however protected on paper—appeared unsafe and psychologically untenable.

Why the Plan Never Took Off?

What emerges from these two interventions—Jagmohan’s appeal in March and Mufti Sayeed’s directive in April—is a rare moment of policy convergence. For a brief period in 1990, Raj Bhavan and the Union Home Ministry were aligned in their assessment that the displacement of Kashmiri Pandits was not meant to become permanent. Both believed the situation could be stabilised, camps secured, and the community retained—or brought back—within the Valley.

That moment, however, proved fleeting.

The proposals never moved beyond intent. Security conditions continued to deteriorate, fear deepened and opposition from within the displaced community hardened. In May 1990, Governor Jagmohan was replaced, bringing an abrupt end to his initiative. By November 10, 1990, Mufti Mohammad Sayeed ceased to be Home Minister. With the departure of both principal actors, the policy lost institutional backing and quietly faded from public discourse.

What was once imagined as a short-term dislocation, possibly resolved by the summer of 1990, has now stretched into over 36 years of displacement. The subject of sending migrants back by 1990, remains one of the most under-reported and least discussed episodes of the Kashmiri Pandit tragedy—raising uncomfortable questions about policy, preparedness and the chasm between intention and outcome.

History often remembers outcomes. It rarely remembers intentions that failed.

This is one such intention—recorded in ink, buried in archives and largely erased from public memory.