(Kashmir Rechords News Desk)

Very few people must be knowing that Swami Vivekananda, one of the most popular monks and spiritual leaders of India was denied a piece of land for establishing a Monastery and a Sanskrit College in Kashmir!

Looks unbelievable, but this shocking incident dates back to Swami Vivekananda’s second visit to Kashmir in 1898 when Maharaja Pratap Singh, who treated him with utmost respect, during the course of discussions, wanted him to choose a tract of land for establishing a Monastery in Kashmir in order to give young people training in non-dualism.

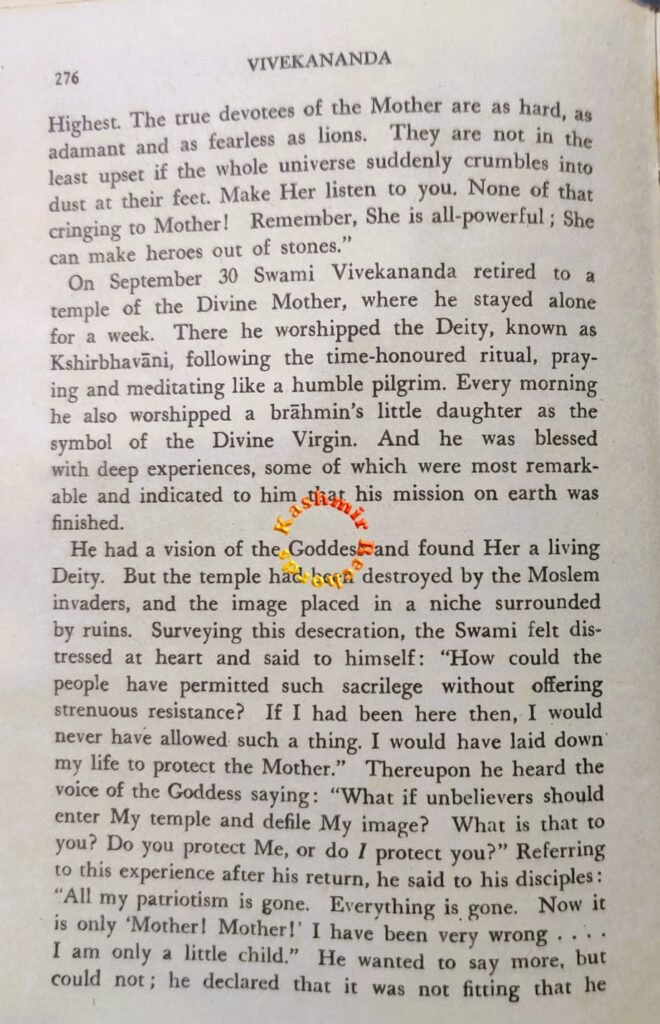

Despite the selection of the land and the submission of the proposal to the British Resident for approval, the same was denied as the British Agent had refused to grant land for establishing a Monastery and a Sanskrit College in Kashmir for unknown reasons. When the same was communicated to Swami Vivekananda, he had accepted the whole thing philosophically.

British Residency was established on September 25, 1885 during the rule of Maharaja Pratap Singh. Sir Oliver St. John was appointed the first British Resident in Jammu and Kashmir.

Vivekananda :A Biography

There is the mention of this shocking incident in a Book “Vivekananda :A Biography’’, written by Swami Nikhilananda at page number 271. According to the Book, published by Advaita Ashrama, Calcutta in January 1953, Swami Vivekananda during his stay in Kashmir (August 8 to September 30, 1898), had felt an intense desire for meditation and solitude. Upon the insistence of Maharaja of Kashmir, the land was identified but a month later, following the refusal to grant the same, Swami’s devotion was later directed to Kali, the divine Mother.

Apart from this incident, the biographer also elaborately discusses Swami’s visit to many parts of Kashmir, including Kheer Bhawani Tulmulla, visit to Amarnath Cave, stay in Srinagar and his meetings with different sections of society there.

It was first time on 10 September 1897, when this great saint visited Srinagar for a short duration. The Swami had left Srinagar for Baramulla and reached Murree on October 8 and from there to Rawalpindi on October 16, 1897.

The second visit of Swami Vivekananda to Kashmir (June to October, 1898) was more eventful. This time a party of Europeans was accompanying him. Prominent among them was Sister Nivedita. During this period, he visited many places of religious and historical importance like Shankaracharya Hill, Hari Parbat, Martand, Panderthan, temples of Avantipora, Bijbehara, Mughul Gardens of Nishat and Shalimar, besides shrines of Shri Amarnath Ji Cave and Mata Kheer Bhawani in Tulmulla. The period from June 22 to July 15, 1898 was spent by Vivekananda and his western disciples in houseboats (dungas) on the Jhelum, in and around Srinagar.

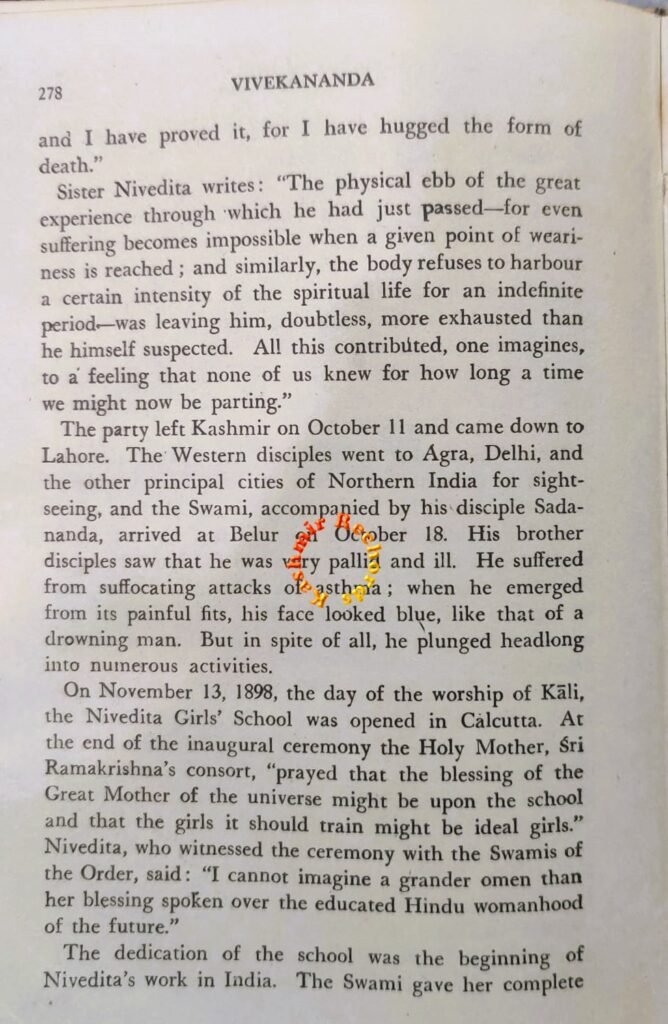

The party had left Kashmir on October 11, 1898 and came down to Lahore. Swami Ji reached Belur Math on October 18, 1898.

About the Biographer

Swami Nikhilananda (1895–1973), the author of `Vivekanda: The Biography” was born as Dinesh Chandra Das Gupta. He was a direct disciple of Sri Sarada Devi. In 1933, he founded the Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Centre of New York, a branch of Ramakrishna Mission, and remained its head until his death in 1973. An accomplished writer and thinker, Nikhilananda’s greatest contribution was the translation of Sri Sri Ramakrishna Kathamrita from Bengali into English, published under the title `The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna’ (1942)