A Bible in Kashmiri Sharda Script!

By : Kanwal Krishan Lidhoo*

In the dusty corners of religious and linguistic history lies a remarkable story—one that links a Bengali riverside mission, a Kashmiri script “Sharda’’ on the verge of extinction, and a Bible that almost nobody read!

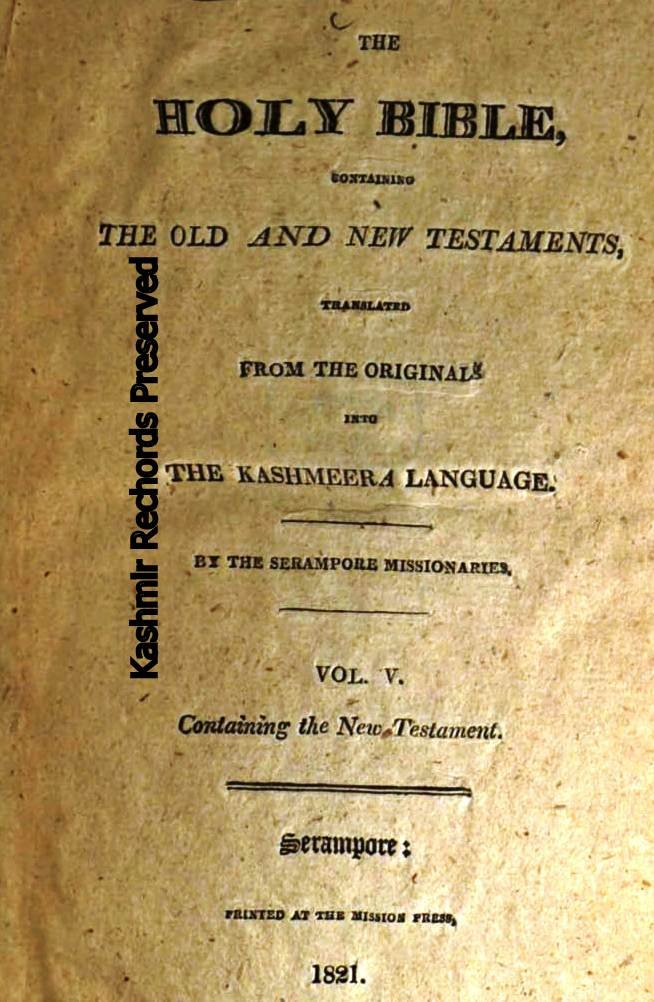

Few people today know that the first-ever translation of the Holy Bible into Kashmiri was printed not in Kashmir, but in the colonial town of Serampore, near Calcutta, in the year 1821. And even fewer know that this translation was rendered not in the now-dominant Perso-Arabic script, but in Sharda—an ancient script once used by Kashmiri Pandits to write Sanskritic texts.

This is the story of that Bible—and the men who tried to bridge two spiritual worlds with a single, sacred book.

Serampore: Where Faith Met Philology

The tale begins at the Serampore Mission, founded in 1800 by three English Baptists—William Carey, Joshua Marshman and William Ward. These missionaries believed that the word of God should be available to every Indian in their own language. Working out of a quiet Danish trading post on the banks of the Hooghly River, they launched what would become one of the most prolific translation projects in the world.

Among them, William Carey stood out—not just as a missionary, but as a linguist, educator and reformer. Carey was convinced that the key to evangelization in India lay in the power of the vernacular. Over time, he helped translate the Bible into more than two dozen Indian languages, including Bengali, Oriya, Marathi, Punjabi, Assamese, and Hindi.

One of the most ambitious and unusual undertakings was his attempt to translate the New Testament into Kashmiri—a language that few British scholars had even heard of at the time.

Why Kashmiri—and Why Sharda?

Carey’s Kashmiri translation was rooted in a fascinating, albeit impractical, choice. While the spoken language of the Valley had begun adopting Perso-Arabic script due to Muslim majority influence, Carey chose the older Sharda script. Derived from Brahmi and closely associated with Hindu scholarship in Kashmir, Sharda had by then fallen into near obscurity.

Carey’s reasoning was both spiritual and strategic. He hoped to reach the intellectual elite of Kashmir, particularly Kashmiri Pandits, who still revered the ancient script. The aim was not mass appeal, but a high-minded dialogue—to reach the minds and hearts of those who shaped religious discourse in the region.

The Translator from Mattan, Kashmir

To carry out the translation, Carey enlisted Thakur Khaar, a Kashmiri scholar likely from Mattan, a town renowned for its ancient temples and centers of learning. The collaboration between Carey and Khaar resulted in a deeply unique manuscript—not just a Christian text, but one steeped in the cultural and spiritual idioms of Kashmir.

Before the scripture begins, Khaar included a Sanskritic invocation, seeking the blessings of Lord Krishna and Lord Shiva. His foreword, rendered in lyrical Kashmiri, reflects a syncretic spirit rarely seen in religious texts of the time.

A translation of the original prologue reads:

“Sacred Divine Words

A Humble Offering

Just as in a garland of flowers no petal is greater or lesser than another, so too is the word of God.

By Thakur Khaar

(Dedicated to the devotion of Upendra)

Let Kumar Bhatta or the scholars of Bhattika scripture kindly accept this Book.

May the Lord’s Grace Always Remain.”

It was an extraordinary moment—where a Christian message entered Kashmir through the doorways of Hindu metaphor, delivered in a script known only to a dwindling few.

A Quiet Launch, a Quieter Reception

The Sharda-script Kashmiri Bible was printed in 1821, but its journey was short-lived. By that time, Sharda had faded from daily use, and most Kashmiri readers had moved to Persian or, increasingly, Urdu.

As a result, the book had almost no readership in the Valley. Very few copies made it to Kashmir at all. The Bible remained, essentially, a beautiful linguistic artifact—an academic marvel, but a practical failure.

Rev. Newton’s Encounter in Ludhiana

Evidence of the text’s obscurity surfaces again in 1838, in the writings of Rev. John Newton, a missionary stationed in Ludhiana. He recorded a rare moment when two groups of Kashmiri Brahmins, then living in Punjab, visited him and asked for religious books.

“I was gratified to find they could read and understand Dr. Carey’s Kashmiri Testament,” Newton wrote. “But such readers are rare. The majority of Kashmiris are Mohammedans who use the Persian script. Carey’s version, though brilliant, was lost in translation.”

It was a poignant acknowledgement. A translation crafted with care and reverence had missed its moment, reaching only a handful of readers—most of them outside Kashmir.

Though the Kashmiri Bible remained unread, it was part of a wider legacy that continues to inspire.

William Carey (1761–1834) was more than a missionary. He was a social reformer who campaigned against sati, advocated for women’s education, and translated the Ramayana into English. He also founded Serampore College, one of India’s oldest degree-granting institutions.

Carey’s Kashmiri translation may not have changed lives, but it showed his belief in the power of language to transcend boundaries—and his respect for India’s ancient literary traditions.

A Lost Bridge Between Faiths

Today, the Sharda-script Kashmiri Bible remains a rare specimen in museum collections and missionary archives. But it tells us something profound.

It is a story of missed connections and unfulfilled intentions—but also of deep cross-cultural respect. A moment when a Western missionary, a Kashmiri Brahmin, and a forgotten script together tried to speak across religious divides.

Even in failure, their effort stands as a quiet, poetic testimony: that faith, language, and dialogue—when rooted in mutual respect—can build bridges, even if history forgets to walk across them.

- Kanwal Krishan Lidhoo is a noted Broadcaster, Author and acclaimed Translator approved by Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi. He is a Founding Director of Kashmir Rechords Foundation.

Comments

Great work. It is a revelation. Thanks for bringing it out.

Thanks for the work.

Chaman Lal Raina

My good wishes to the “Kashmir Rechords”.A very wonderful documentation. Is it the New testament and /or the Old Testament?

Kashmir Rechords

Thanks for your words of appreciation. It is a new testament.