(Kashmir Rechords Exclusive)

Every year on September 14, Kashmiri Pandits observe Martyrdom Day to remember their leaders and loved ones lost in the conflict of 1989-1990. One name often evoked is Pt. Tika Lal Taploo, a prominent Pandit leader whose assassination on September 14, 1989, marked the beginning of a tragic chapter that culminated in the mass exodus of Kashmiri Pandits on January 19, 1990. However, the martyrdom of the community extends far beyond Taploo’s death. The true tragedy lies in the loss of countless Pandits who perished far from their homeland, denied the dignity of being cremated in the sacred land of their ancestors.

For the displaced community, it wasn’t just about losing their homes, but also the final connection to their heritage—the right to rest in their own land.

Rajinder Park: A Refuge for Grief and Last Rites

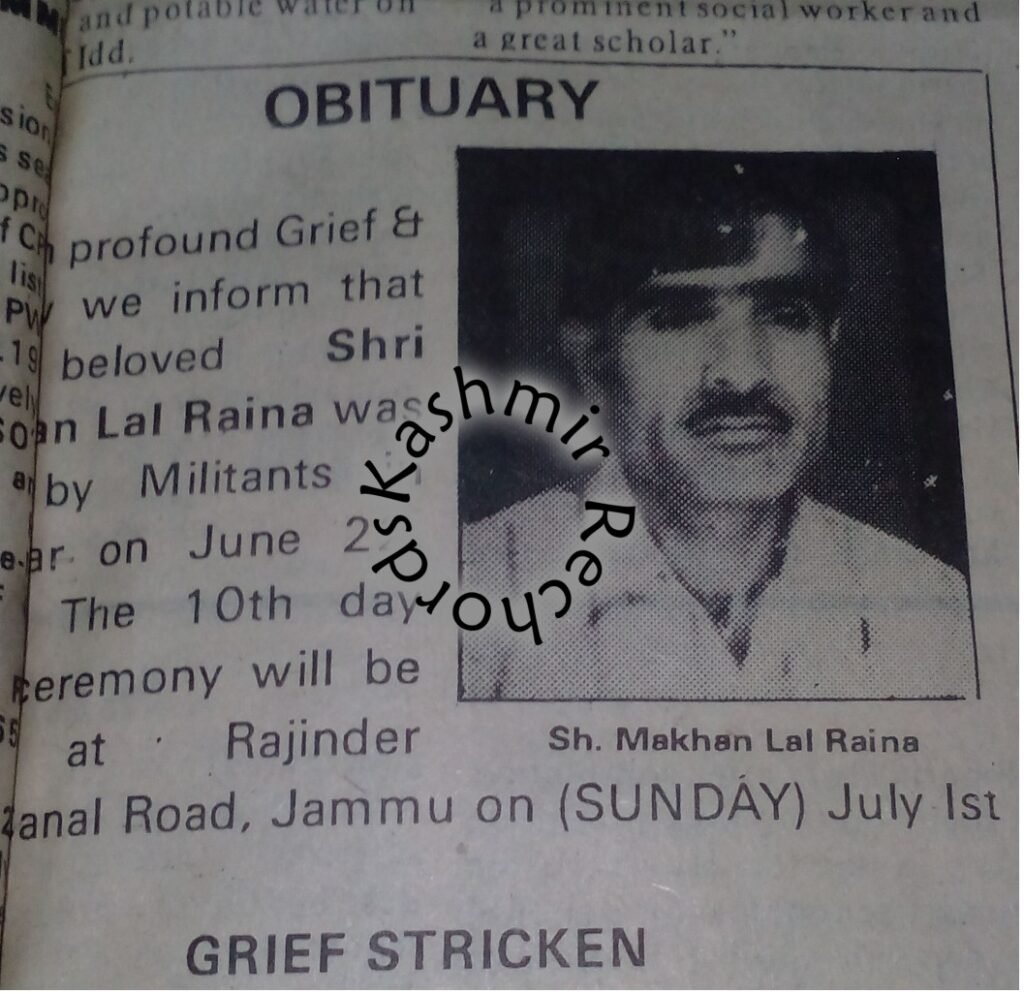

In the early 1990s, the Pandit community, thrust into exile in Jammu, faced an overwhelming dilemma. With no place to gather, no traditional cremation grounds, and a communication vacuum in an era before social media, they were left in disarray. Unlike today, when a death can be shared instantly on platforms like WhatsApp, Kashmiri Pandits relied on local newspapers to spread the heart-breaking news of terrorist killings in Kashmir. The absence of a central address, a shared space for collective grief, further deepened the community’s alienation.

It was in this void that Rajinder Park, located on Jammu’s Canal Road, emerged as an unintended sanctuary. Originally a public space, it transformed into a vital gathering place where Kashmiri Pandits could come together, mourn their dead, and perform the last rites, the Tenth-Day Kriya. Families, who had fled the horrors of their homeland, now found themselves in Rajinder Park, a place that soon became symbolic of their new reality—an exile with no true home.

A Landmark of Resilience

For the older generation of Kashmiri Pandits, Rajinder Park is etched deeply in their memory. It became a witness to their collective sorrow, where the sounds of sobbing and whispered prayers replaced the serenity that once filled the park. It served as a space of solace, where families would honor their deceased and perform rituals, which were traditionally reserved for the sacred Ghats of Kashmir. In the absence of their homeland, Rajinder Park became the place where they could cling to their cultural traditions, even if it was in the heart of an unfamiliar city.

The park played this critical role for years until more formal Tenth Day Kriya Ghats were established at Muthi , Tawi Bridge in Jammu and at the banks of Chenab near Akhnoor Town. Yet, for many in the community, Rajinder Park remains more than a temporary refuge; it is a powerful reminder of those early years of displacement when Kashmiri Pandits were forced to navigate unimaginable grief and loss in exile.

While many of the younger generation may not know its significance, Rajinder Park Jammu stands as a monument to the resilience, sacrifice, and endurance of the Kashmiri Pandit community. For those who lived through the harrowing events of 1990, the park is more than just a physical space—it is a testament to the strength of a people who, even in the depths of despair, found ways to preserve their dignity and cultural identity.

For every Kashmiri Pandit who died far from home, Rajinder Park, Jammu stands as a poignant reminder that their sacrifices, and the shared history of their community, will never be forgotten.