(Kashmir Rechords Exclusive)

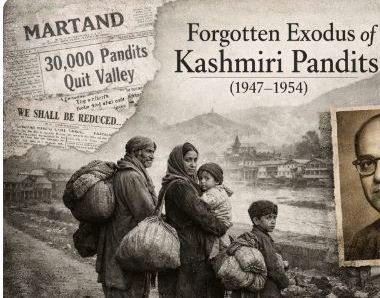

When the tragic mass exodus of Kashmiri Pandits in 1990 is recalled, it is often framed as the first great rupture in the community’s modern history. Some narratives go further back, listing seven migrations across centuries. Yet, buried deep in archives and largely absent from public discourse, lies a crucial, well-documented migration that took place soon after Independence, between 1947 and 1954, when nearly 30,000 Kashmiri Pandits were compelled to leave Kashmir.

This was not a sudden flight triggered by militancy, but a slow, grinding exodus caused by humiliation, neglect, economic strangulation and discriminatory governance in the immediate aftermath of Jammu and Kashmir’s accession to India.

A Migration History That Was Silenced

Ironically, this early post-Partition migration was not documented by a partisan critic of Kashmir’s leadership, but by Prem Nath Bazaz—a figure revered by many Kashmiri Muslims as a secular intellectual and nationalist, yet viewed with suspicion by large sections of the Kashmiri Pandit community for his political positions.

Bazaz, despite being banished from his own homeland by the Sheikh Abdullah–led regime and prohibited from entering the State, emerged as one of the most meticulous chroniclers of the Kashmiri Pandits’ plight during this formative period.

Voice of Kashmir: An Uncomfortable Record

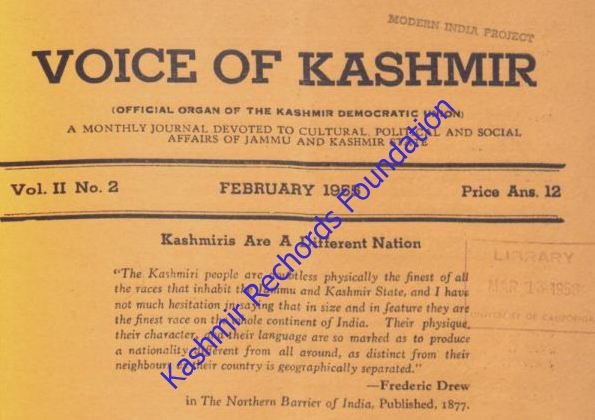

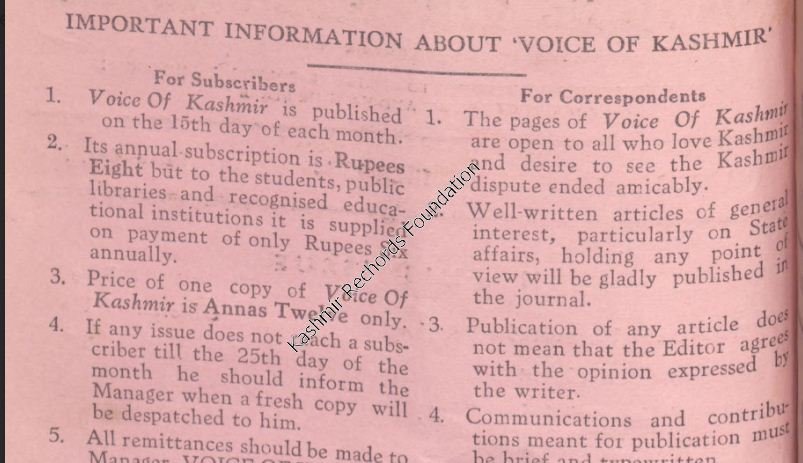

After relocating to Delhi in the early 1950s, Bazaz founded and edited a monthly journal, Voice of Kashmir, published from Karol Bagh, Delhi. The journal, issued on the 15th of every month, became a rare platform documenting Kashmir’s political, social and economic upheavals after 1947.

Priced modestly—twelve annas per copy, with subsidised subscriptions for students and libraries—Voice of Kashmir carried essays that many found deeply inconvenient, particularly those exposing the systematic marginalisation of Kashmiri Pandits under the new dispensation.

The Martand Testimony: Numbers That Cannot Be Ignored

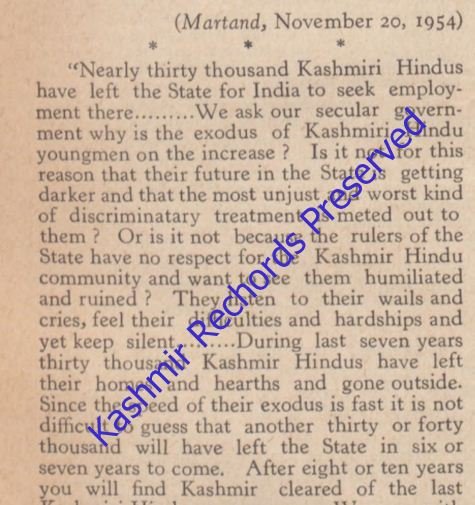

In several articles, Bazaz reproduced reports from The Martand, the official organ of the Kashmiri Pandits Conference. Quoting Martand issues dated November 20 and 23, 1954, Bazaz recorded a stark fact:

Nearly 30,000 Kashmiri Hindus had migrated from the State between 1947 and 1954, primarily in search of livelihood and dignity.

The Martand report warned ominously that if the trend continued, “Kashmir will be vanished of Kashmiri Pandits” within a decade—a prophecy that tragically materialised first during the 1986 Anantnag riots and finally in the 1990 exodus.

Agrarian Reforms and Economic Dispossession

Central to this early migration was the controversial Agrarian Reforms Act, implemented under the regime of Sheikh Abdullah. While projected as a progressive land-to-the-tiller reform, its execution proved devastating for Kashmiri Pandits—particularly village-based agriculturists.

Bazaz documented how:

- Pandit landowners were prevented from tilling their own land

- Lands were forcibly or selectively transferred to Muslim tenants

- Legal protections were applied unevenly and politically

Villages such as Sarsa, Murran (Anantnag district) and parts of North Kashmir were specifically cited, where Pandits faced threats, intimidation and eviction, even when court cases were pending.

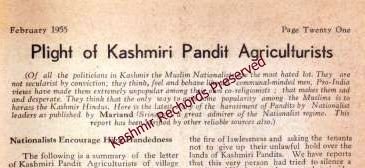

“Plight of Kashmiri Pandit Agriculturists” (February 1955)

In a February 1955 article titled “Plight of Kashmiri Pandit Agriculturists”, reproduced in Voice of Kashmir, Bazaz highlighted how:

- Large estates were abolished, but Pandits were denied fair retention limits

- National Conference cadres allegedly encouraged tenants to illegally occupy Pandit land

- Laws were enforced selectively, eroding the economic base of the community

A letter from Pandit agriculturists of Murran questioned why the government refused to act against illegal occupants—raising serious concerns about state-sanctioned discrimination.

Education, Representation, and Humiliation

Another disturbing dimension was educational discrimination. Bazaz criticised the policy of bracketing Kashmiri Pandits with Hindus of Jammu while extending separate concessions to Sikhs, arguing that such categorisation undermined national unity and deepened alienation.

The articles describe Pandit villagers as poverty-stricken tillers, struggling for survival in their own homeland, while being treated with institutional indifference and contempt.

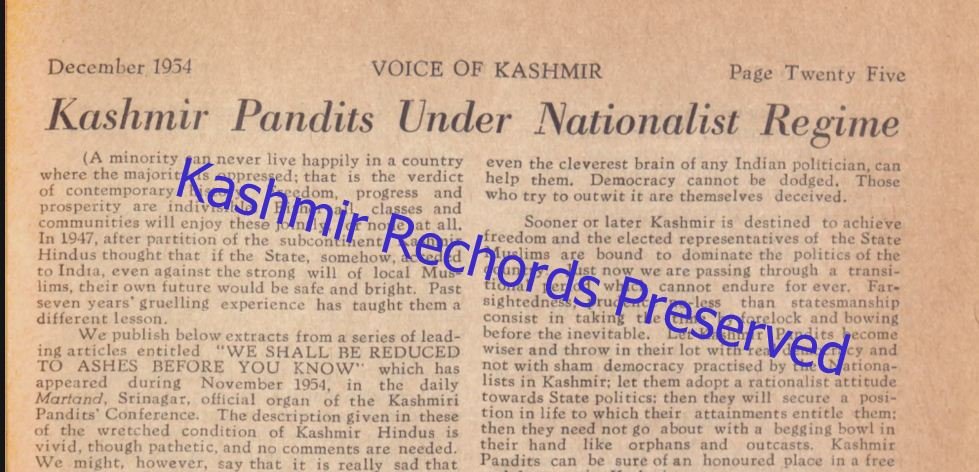

“We Shall Be Reduced to Ashes Before You Know”

Perhaps the most chilling warning appeared in a November 1954 Martand article, republished by Bazaz under the title:

“WE SHALL BE REDUCED TO ASHES BEFORE YOU KNOW”

The piece vividly described the wretched and degrading conditions of Kashmiri Hindus and issued a stark caution: blind support to the Indian government’s Kashmir policy and the National Conference would lead the community to ruin.

Bazaz urged Kashmiri Pandits to abandon “sham democracy” and align with genuine democratic principles, warning that otherwise they would be reduced to “begging bowls in their hands like orphans and outcastes.”

A Historian Against His Own Rejection

The irony is painful. Prem Nath Bazaz, though rejected by many Kashmiri Pandits for his ideological differences, preserved their most uncomfortable truths. His journal—though discontinued in 1955 and poorly archived—remains one of the rarest primary sources on the first post-Independence displacement of Kashmiri Pandits.

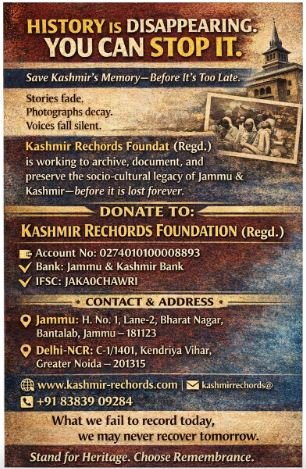

Institutions like Kashmir Rechords, which have preserved surviving issues of Voice of Kashmir, are therefore safeguarding not just documents, but a suppressed chapter of history.

Reclaiming a Lost Chapter

The migration of 1947–1954 was not incidental—it was foundational. It hollowed out the Pandit presence in rural Kashmir, weakened their economic roots and set the stage for future catastrophes. Ignoring this episode distorts the historical continuum and reduces 1990 to an isolated tragedy rather than the culmination of a long, documented process.

To understand the Kashmiri Pandit question honestly, this first forgotten exodus must be restored to collective memory—not as hearsay, but as history written by those who witnessed it, recorded it, and warned the nation in time.