(Kashmir Rechords Exclusive)

Amit Bhat (name changed) was born on January 20, 1990—a date that arrived with a cry, but also with a crossing.

The day before, his parents, Sarla and Ashok (names changed), had fled their remote village in Kupwara. The night of January 19 had swallowed the Valley in fear. By dawn, there was no choice left—only movement. A family caravan formed in haste: Ashok’s ageing parents, a younger brother, a sister and Sarla, heavy with child. What they carried was little; what they left behind was everything.

The journey from Kupwara to Jammu stretched through dread. Sopore. Anantnag. Roads that felt longer than maps admit. A day-long passage through volatility, checkpoints, silence punctured by slogans, and the constant fear of being stopped—or worse. Sarla’s labour pains began on the move. There was no turning back.

They reached Jammu exhausted, stunned, unmoored. Chinore—a rented room in a locality they had never seen, in a region they had never known—became refuge by default. There was no hospital admission waiting, no familiar doctor, no neighbour to call. A local woman from a nearby village was found. She became the midwife. In an alien room, among strangers, Sarla delivered a child. They named him Amit.

He entered the world between exile and uncertainty—born not into a home, but into flight.

A Journey That Arrived Too Soon

Sunita (name changed) and Roshan Lal (name changed) from Budgam had married in 1988. By early 1990, they were expecting their first child—due in March, 1990. Plans had been made, names discussed, a room imagined back home.

Militancy tore through those plans.

Seven months pregnant, Sunita climbed into a truck with her family, carrying whatever could be grabbed in minutes. The Srinagar–Jammu highway became a test of endurance—harsh, serpentine, mountainous. Hours turned into pain. Pain turned into complications. The journey triggered a premature birth. A child arrived too early, shaped by the violence of displacement even before drawing breath.

Invisible Mothers, Uncounted Births

The stories of Sarla and Sunita are not exceptions. They are fragments of a larger, unwritten chapter.

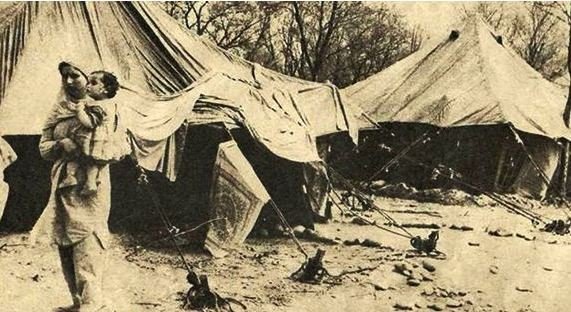

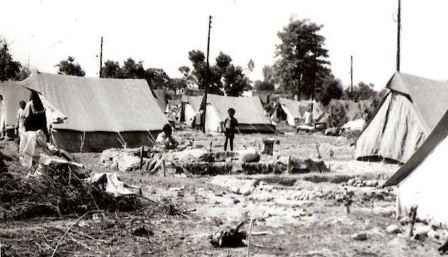

Scores of Kashmiri Pandit women—first-time mothers and otherwise—were pregnant when they fled. Some delivered in tents. Some in overcrowded camps. Some in one-room rented accommodations shared by joint families. Some on hospital ward floors already overwhelmed. Children were born in Jammu’s Mishriwalla, Jhiri Muthi Camps, Kathua nd Udhampur’s Batal-Balian and other makeshift shelters—places never meant to cradle new life.

There is no register of these births.

No column in any report records labour pains on highways, or deliveries without doctors, or mothers who crossed districts and destinies while carrying life inside them. No archive counts how many conceived in Kashmir and delivered in exile. No ledger remembers their trauma.

And yet, even conservative demographic estimates suggest that dozens—perhaps over a hundred—such births took place between January and August 1990 alone, in camps and cramped rooms across Jammu region.

What History Forgot to Write Down

These children are now in their thirties. They carry birth certificates stamped with places their parents had never imagined calling home. Their first address was exile. Their first inheritance was loss.

History remembers January 1990 for what it destroyed.

It rarely pauses to ask what was born in its aftermath.

Amit’s first cry did not echo in Kupwara. It rose in a rented room in Chinore—thin, fragile, defiant. It said what his parents could not afford to say aloud then:We are still here.

A Call to Remember

Kashmir Rechords appeals to all parents who faced the trauma of becoming mothers and fathers while in transition, and to all Kashmiri Pandit boys and girls born between January 1990 and August 1990, to share their stories.

Your testimonies will help compile a long-ignored record of pain, resilience and survival—so the world can finally hear what exile did to birth itself.

Real names will not be disclosed if contributors wish anonymity. Contact us at:

📩 kashmirrechords@gmail.com

📩 support@kashmir-rechords.com

Some histories survive only when those who lived them speak.