(Kashmir Rechords Exclusive)

Remembering September 14

Every September 14, Kashmiri Pandits bow their heads in silence, observing Martyrdom Day—a day heavy with grief and memory. It marks the assassination of Pt. Tika Lal Taploo, a towering community leader whose life was cut short on September 14, 1989. His killing was not just the silencing of a voice; it was the ominous prelude to the mass exodus that would follow on January 19, 1990. For Pandits, Taploo’s martyrdom symbolized the violent unraveling of their very existence in the land of their ancestors. Soon after, Judge Nilkanth Ganjoo, Lassa Kaul, Sarla Bhat and countless others joined the ranks of martyrs, their lives extinguished by the same tide of terror.

But the story of Kashmiri Pandit martyrdom does not end with these names alone. It extends to thousands of ordinary men, women and children—martyrs in their own right—who lost their lives in exile, denied even the sacred dignity of their final rites in Kashmir’s soil. Whether killed by bullets in their homeland or by sunstroke, snakebite and disease in the punishing heat of refugee camps, each one carried the same burden: a forced uprooting from home, history and heritage.

A Dispersed Grief

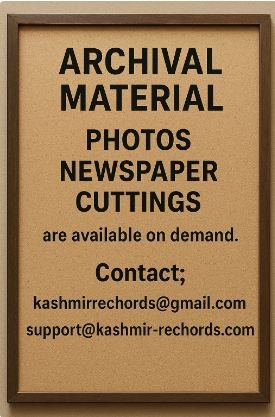

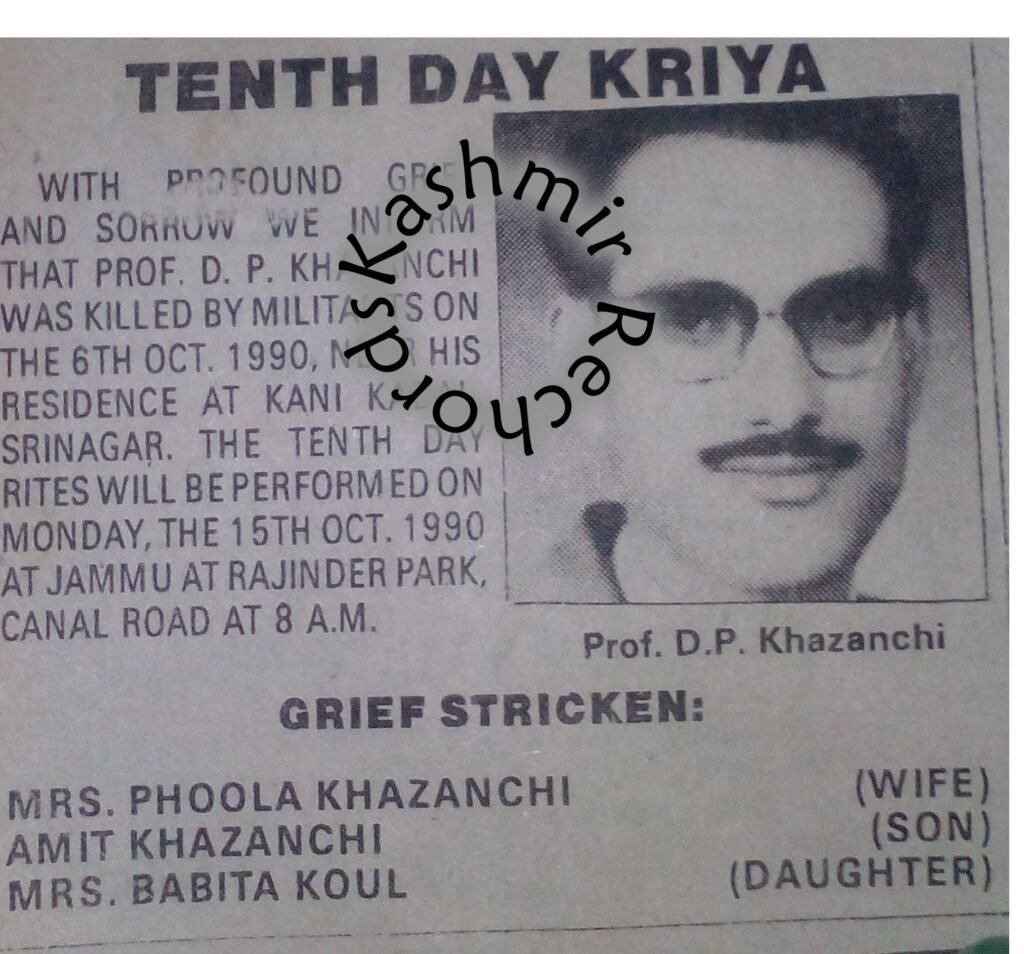

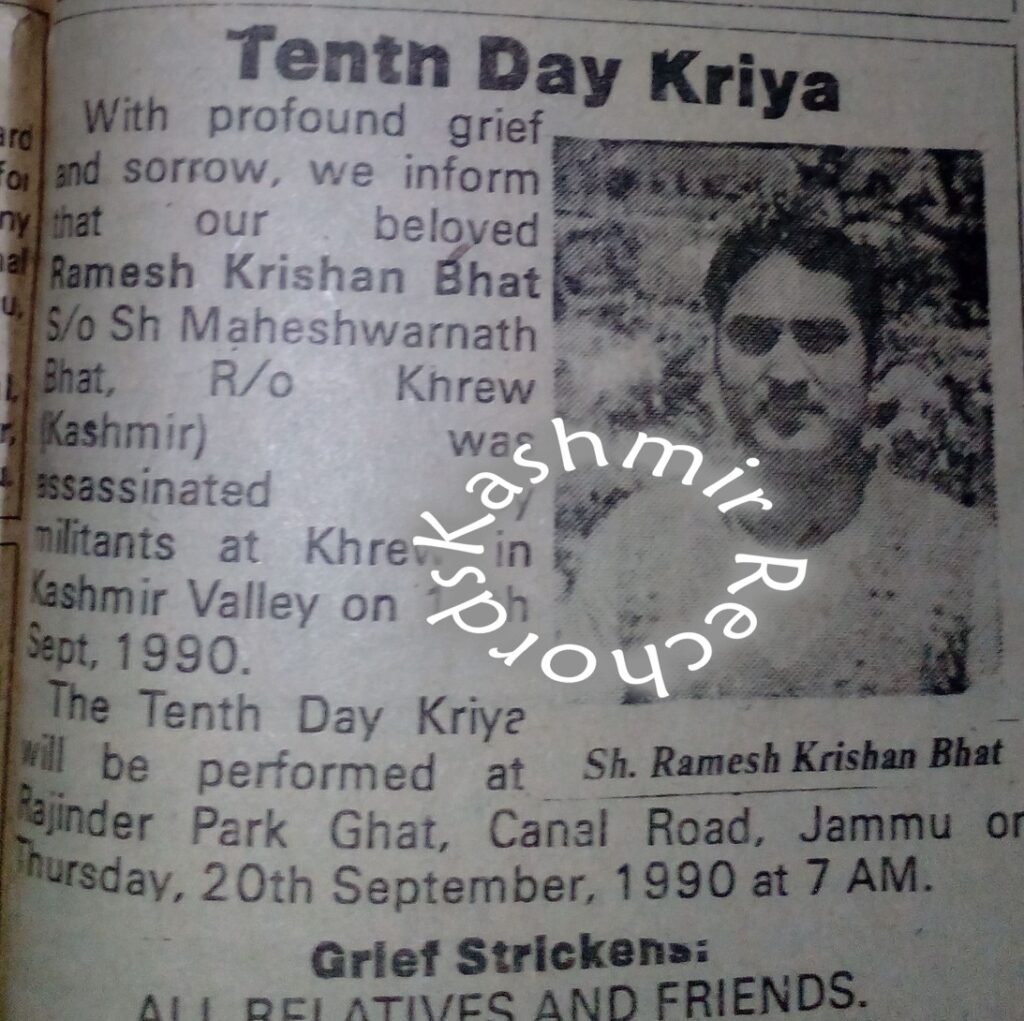

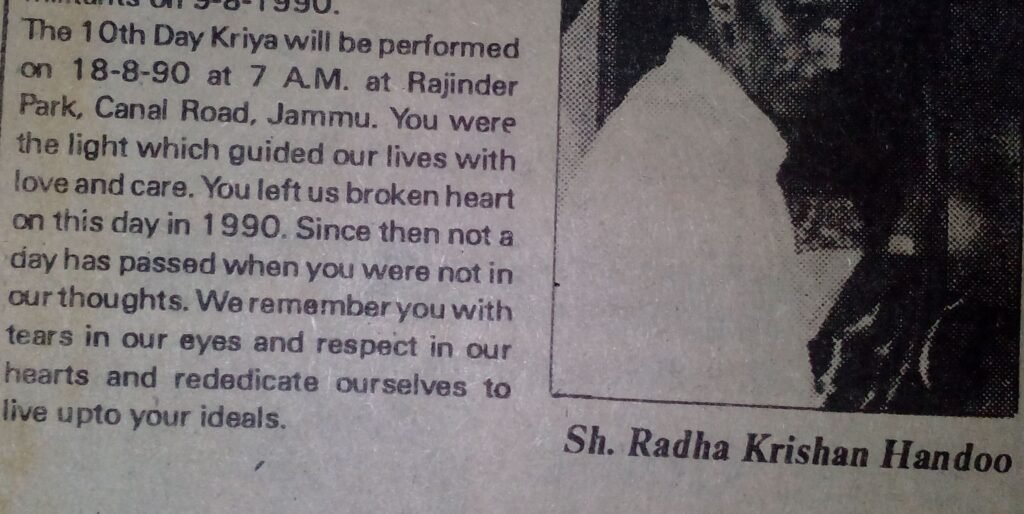

In the early days of migration, there was no central place for Pandits to gather, mourn, or carry out rituals. WhatsApp and digital networks did not exist. News of a death—whether by militant violence or the cruel hand of exile—spread through small columns in local newspapers. The community, disoriented and scattered, had nowhere to cry together, nowhere to console each other.

Out of this void emerged Rajinder Park on Canal Road in Jammu. What began as a makeshift refuge soon became a solemn sanctuary. Here, under the open sky, Pandits performed the last rites of their loved ones. It was at Rajinder Park that the Tenth-Day Kriya, once performed at Kashmir’s sacred river ghats, was now carried out in exile. Ashes that should have mingled with the waters of the Vitasta (Jhelum) were instead consigned to distant flames, leaving behind a haunting emptiness.

For the older generation, Rajinder Park remains etched into memory as a witness to collective sorrow. For the younger, it is a fading landmark—an unfamiliar place whose soil carries the invisible tears of their parents and grandparents. Yet, it endures as a symbol of survival: a reminder that even in displacement, traditions found a way to breathe.

A Legacy of Waiting

More than three decades later, Kashmiri Pandits continue to live with an unhealed wound. Every death in exile feels like a second exile—a departure from this world without the comfort of returning to ancestral land. The yearning to go back remains alive, yet no concrete of permanent roadmap of return has materialized. Those who orchestrated the tragedy still walk free, cases are endlessly “reopened,” and assurances of justice echo hollow.

And so, every September 14, when candles are lit for Tika Lal Taploo and all the martyrs, the flame is more than remembrance—it is resistance. It is a vow that the story of the unseen martyrs, denied even their last embrace with Kashmir’s soil, will not fade into silence.

Because their legacy is not only one of loss—it is one of resilience. A resilience that continues to define Kashmiri Pandits, even as every prayer ends with the same hope: To return, and to rest, in the homeland that still beats in their hearts.