(Kashmir Rechords Exclusive)

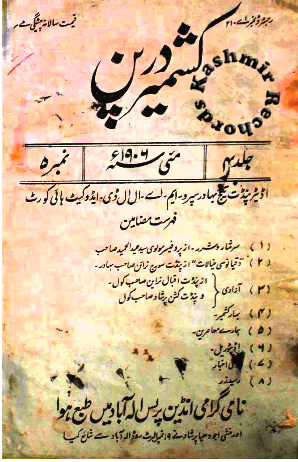

Very few know that more than a century ago, in the bustling city of Allahabad, a remarkable cultural experiment was taking shape. In 1902, from the presses of Nami Grami Indian Press at Dara Ganj, a bilingual monthly magazine called Kashmir Darpan was born. This 50-page publication, printed in both Urdu and Hindi, became a lifeline for Kashmiri Pandits scattered across British India. At a time when communication was slow and long-distance travel rare, Kashmir Darpan bridged distances and brought together a community yearning to remain connected with its roots.

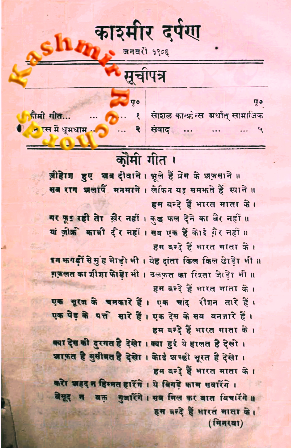

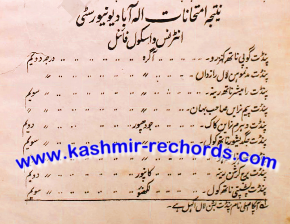

Far from being a mere magazine, Kashmir Darpan became a chronicle of Kashmiri, and provided space for those interested in literature to share their prose and poetry. Each issue served as a community diary, announcing births, marriages, deaths, student achievements, job postings and transfers. To ensure inclusivity, ten pages of every edition were dedicated exclusively to Hindi-knowing members of the community. For many, it felt as if every edition was a letter from home — a packet of news from Lahore to Dhaka, from Srinagar to Jodhpur — uniting far-flung families in spirit.

Access to editions from 1903 to 1906 by Kashmir Rechords reveals just how far-reaching its impact was. The magazine connected Kashmiri Pandits living in Calcutta, Dhaka, Jodhpur, Hoshiarpur, Lucknow, Varanasi, Jalandhar, Lahore, Sialkot, Amritsar, Srinagar and Jammu. For a community that had migrated in search of education, work and opportunity, Kashmir Darpan became a cultural anchor, a reminder of shared heritage, and a tool for identity preservation.

The driving force behind this publication was Pandit Tej Bahadur Sapru, one of India’s most respected lawyers and public figures, ably supported by Manohar Lal Zutshi who managed the operations. Sapru invited some of the finest minds of the time to contribute to the magazine, including scholars, poets and writers like Brij Narayan Chakbast, Kripa Shanker Koul, Dharam Narayan Raina, Iqbal Narayan Gurtu, Syed Abdul Majid, Krishan Prasad Kaul, Prasaduman Krishan Kitchloo, Kanhaya Lal Shangloo ‘Mubarak’, and Sheikh Abdul Qadir. Together, they transformed the magazine into a mirror of Kashmiri intellectual and cultural thought — living up to its name, Darpan, meaning “mirror.”

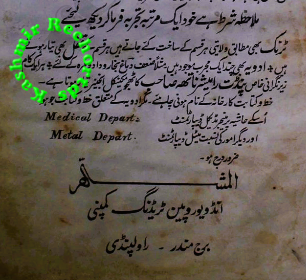

The magazine’s pages also reveal a progressive agenda. It championed the cause of women’s education among Kashmiris and reported the establishment of a girls’ school exclusively for Kashmiri students. Sapru through his editorials and write-ups frequently encouraged the community to take up business ventures instead of relying solely on government jobs. The publication highlighted successful entrepreneurs such as Pt Dharam Narayan Raina, Razdan Brothers of Amritsar, Saheb Brothers of Dhaka, Jeevan Nath Ganjoo who owned the Swadeshi Stationery Shop, and Ghulam Hussain & Brothers of Karachi. One particularly inspiring story celebrated Pandit Rameshwar Nath Kathju, a mechanical engineer, who was encouraged to set up the Indo-European Trading Company at Brij Mandir in Rawalpindi — a venture that became renowned for medicines, metal boxes, and heavy-duty locks.

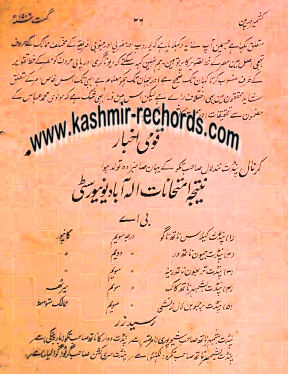

What made Kashmir Darpan truly special was the way it was sustained — not by corporate advertisements, but through annual subscriptions and voluntary contributions from members of the community spread across British India. Readers and patrons such as Nand Lal Tickoo of Karnal, Shyam Lal Chaku of Lucknow, Prithvi Nath Razdan of Jodhpur and Shambu Nath Hakhu of Ajmer kept the presses running. Its circulation was wide enough for copies to be available in leading libraries and educational institutions across the United Provinces, a testament to its popularity and reach.

The magazine also played a humanitarian role when devastating floods struck Kashmir in 1905. Sapru used its pages to make repeated appeals for relief contributions and published regular updates in each issue. The funds collected were later handed over to the Governor of Kashmir, proving how a community-driven publication could turn into a lifeline for those in distress.

Pandit Tej Bahadur Sapru is today remembered as one of the greatest lawyers and constitutional experts of India, a freedom fighter, and a member of the Viceroy’s Council. Yet his work through Kashmir Darpan reveals another side of him — that of a man deeply committed to his roots. Born in Aligarh on 8 December 1875 to Ambika Prasad Sapru and Gaura Sapru (née Hakhu), Sapru belonged to a distinguished Kashmiri Pandit family. His career was illustrious: he worked as a lawyer at Allahabad High Court, where Purushottam Das Tandon served as his junior, later became Dean at Banaras Hindu University, and served in the Legislative Council of the United Provinces, the Imperial Legislative Council, and as Law Member in the Viceroy’s Council. But his efforts through Kashmir Darpan — encouraging education, entrepreneurship and social reform — were equally significant.

Sir Tej Bahadur Sapru passed away on 20 January 1949 in Allahabad, seventeen months after India gained independence. His legacy, preserved through the surviving editions of Kashmir Darpan, some preserved by Kashmir Rechords, remains a cornerstone in the cultural history of the Kashmiri Pandit community. For today’s Kashmiri Pandits, dispersed across the globe after the 1990 exodus, this century-old magazine stands as a reminder that community-driven media has always been a powerful tool to preserve identity, nurture cultural memory and strengthen bonds that transcend geography.