(Kashmir Pandit Exclusive)

In the late 19th century, a myth took root that Kashmiri Pandits, a so called educated and affluent community, monopolized top bureaucratic positions under Maharaja Pratap Singh. Contrary to this belief, the majority of Kashmiri Pandits, between 1890 and 1910, were struggling with poverty and educational backwardness. Most were relegated to low-paying jobs, far removed from the narrative of success.

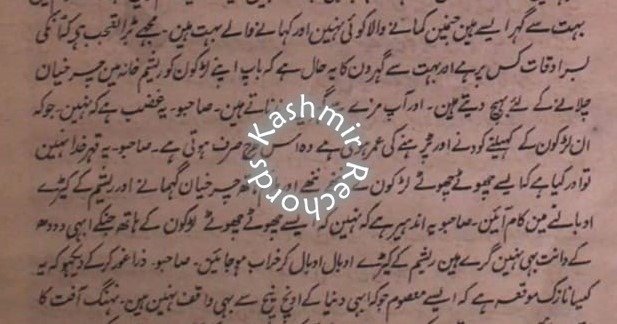

Pandit Gopi Nath Saheb, a leading figure in the Kashmiri Reform Association, shattered these misconceptions in a landmark speech in 1904. Addressing students at Hindu College, Srinagar, his bold words revealed a grim truth about the community’s condition, which had been overlooked. The speech, later published in influential periodicals edited by statesman Tej Bahadur Sapru, cast a glaring light on the struggles of Kashmiri Pandits.

Spiritual and Economic Struggles

Pandit Gopi Nath’s fiery critique exposed a community gripped by spiritual and economic decline. He accused his fellow Pandits of succumbing to the burden of menial jobs, neglecting educational and entrepreneurial opportunities. The Kashmiri Reform Association, founded in 1903 under Pandit Jia Lal Shivpuri, aimed to combat these issues, advocating societal reforms to uplift the impoverished community.

At the time, many Kashmiri Pandits sought economic favours from Punjabi businessmen, abandoning their cultural identity by trading their traditional turbans for Punjabi attire. This cultural shift symbolized a community willing to sacrifice its heritage for survival.

Child Labour and the Silk Factory Scandal

One of the most heart-wrenching aspects of Pandit Gopi Nath’s speech was his criticism of child labour in the Srinagar Silk Factory. Srinagar-based Kashmiri Pandit fathers, driven by poverty, were regularly sending children as young as ten to work in grueling conditions. These children toiled in boiling silkworm cocoons or spinning wheels for meager wages, deprived of education and a brighter future.

He also recalled the 1903 floods, when the destitution of Kashmiri Pandits became tragically evident. Most could not afford basic food grains from Rawalpindi. Meanwhile, Punjabi traders dominated markets like Amirakadal, Zainakadal, and Habbakadal, employing Kashmiri Pandits as commission agents—further reinforcing their economic dependence.

Decline of Education and Lost Opportunities

Gopi Nath’s lament extended to the decline of education among Kashmiri Pandits. While affluent Kashmiri Hindus and Muslims used to send their children to Lahore and Allahabad universities, only a handful of Pandits were pursuing studies in Kashmir. In 1904, only ten Kashmiri Pandits passed the Entrance Examination. By 1906, that number had plummeted to just four. Out of a population of over 60,000 Pandits, ( 1901 Census) this stark decline reflected a crisis in education and aspirations.

For Gopi Nath, this was a tragedy of untold proportions. In his view, Kashmiri Pandits, rather than embracing professions like masonry, carpentry, vegetable selling or tailoring, opted to remain idle, running dilapidated tuck shops that sold items like snuff powder, tobacco or soap—barely making enough to survive.

A Call for Reform

Despite his criticisms, Pandit Gopi Nath was hopeful for change. He called on his community to break the cycle of poverty and leave behind the menial labour of the Silk Factory. Education, he believed, was the key to progress. He also urged the Kashmiri Reform Association to provide scholarships for deserving students and condemned the practice of marrying off young girls to much older widowers.

The speaker implored upon native Kashmiri Pandits, particularly living in Srinagar to find time to pay goodbye to menial silk-worm work in Silk factory. Instead, start reading for which his Association would provide financial assistance to the deserving students. He also laments the exploitation of innocent Kashmiri Pandits whose daughters aged 10 were forced to marry to a widower of 30.

Although the Kashmiri Reform Association was determined to uplift the community, Gopi Nath expressed reservations about the involvement of two prominent British educators like Mr. Moore, the principal of Hindu School, and Mr. Biscoe, the principal of Mission School. He felt their influence, though well-intentioned, could steer the association away from its mission of grassroots reform.

A Legacy of Resilience

Pandit Gopi Nath’s speech remains a timeless reminder of a community’s struggles and its enduring hope for a brighter future. His words not only exposed the harsh realities of his time but also inspired a movement for reform. The Kashmiri Pandit community, despite its hardships, forged a legacy of resilience that continues to inspire future generations.