Roshan Lal Jalla, a Kashmiri intelligence operative, spent 15 years in Pakistani prisons after being captured in 1972. Tortured, disowned, and denied rehabilitation upon his return, his story was documented by The Illustrated Weekly of India and preserved by Kashmir Rechords.

(Kashmir Rechords Exclusive)

Cinema loves its spies—silent men slipping across borders, bruised but unbroken, returning home to gratitude and glory. Films like Dhurrandhar remind audiences that espionage is a game of shadows, courage and sacrifice. But long before the camera found such stories, Kashmir had already lived one—raw, unresolved and devastatingly real Dhurandhar.

In the late 1960s, Roshan Lal Jalla, a young man from Kashmir, crossed into Pakistan on a mission that was never meant to be acknowledged. He went once in 1969, again in 1970 and once more during the 1971 war. Each time, he returned quietly, having done exactly what the Nation had asked of him. There were no medals, no citations—only fresh instructions and an unspoken assurance that the country stood behind him.

That illusion collapsed in 1972

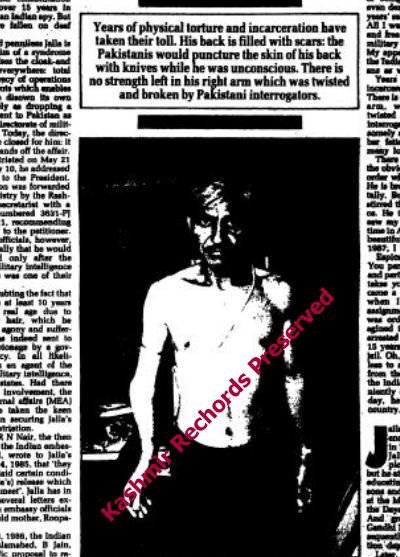

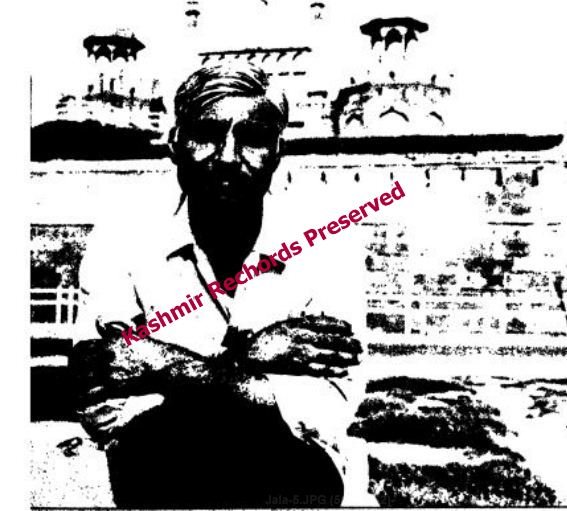

While attempting to return to India, Jalla was captured near the India–Pakistan border. What followed were fifteen years of disappearance—years swallowed by Pakistani prisons, interrogation cells and a system designed not just to extract information, but to erase the human being who possessed it. He was beaten, subjected to electric shocks, stabbed while unconscious, his right arm twisted and broken. The scars never healed, and neither did the damage to his mind. Yet through it all, Jalla did not betray his mission.

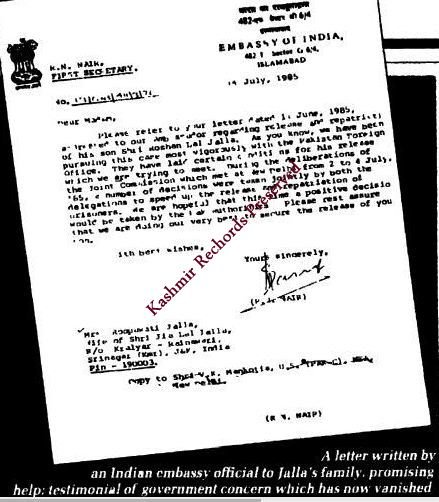

Back home, life unravelled in parallel. His wife Santosh died waiting. His father, Jia Lal Jalla, passed away without knowing whether his son would ever return. His three year son Rajesh grew up without stability or proper education. Only his mother, Roopawati Jalla, living in Kralyar, Rainawari in Srinagar, continued to knock on doors that rarely opened. A letter dated July 14, 1985—from the Indian Embassy in Pakistan—acknowledged that officials were in touch with her while efforts were being made for her son’s release. It was proof, quietly filed away, that the State knew exactly who Roshan Lal Jalla was.

When he was finally released in 1987 as part of an exchange of prisoners, Jalla expected little—but not what awaited him. There was no rehabilitation, no official recognition, no pension. The very agency that had sent him across hostile territory multiple times refused to acknowledge him. He had returned from fifteen years of torture only to discover that, in the eyes of his own country, he no longer existed.

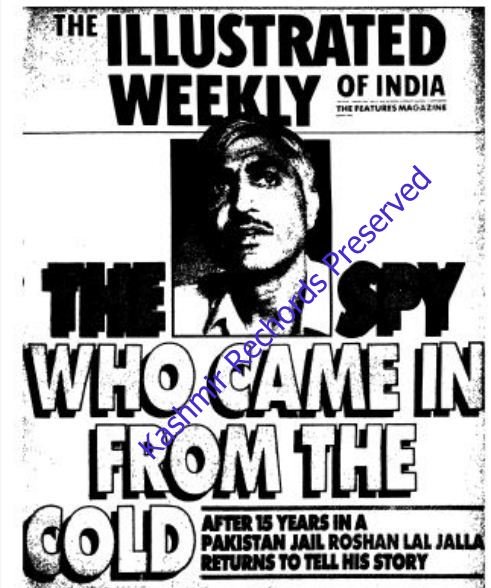

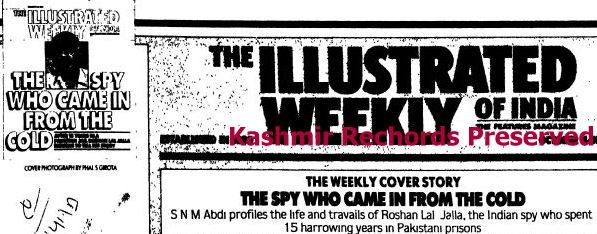

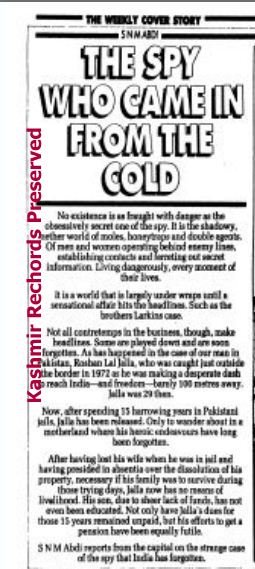

His story might have vanished entirely if it were not documented by The Illustrated Weekly of India, which published a haunting profile titled “The Spy Who Came In From the Cold.” Veteran journalist S. N. M. Abidi, after a five-hour interview, described Jalla as a “hapless victim” of an intelligence syndicate—used when useful, discarded when inconvenient. The article recorded not just his words, but his wounds: knife marks on his back, a broken arm, prematurely grey hair and a haunted stare that spoke of years spent between hope and despair. It also cited testimonies from human rights organisations in Pakistan describing systematic physical torture in jails—details chillingly mirrored on Jalla’s body. The article identifies the agency and the person who used to be in touch with Jalla and later the same very officer disowned him. The article also mentions a particular code jalla was assigned and how he had possessed an Identity Card of Pakistani Rangers designed himself as ‘Sub Inspector” under a Muslim name.

“I gave the best years of my life to the nation,” Jalla told the magazine. He did not ask for honours or compensation. All he pleaded for was survival—medical treatment in a military hospital, a modest pension to live with dignity. He wrote to the Home Ministry. He petitioned even the President of India. Nothing came.

It is here that Kashmir Rechords steps in—not as a narrator, but as a custodian of truth. By retrieving, preserving, and placing in the public domain the rare scanned issue of The Illustrated Weekly of India, Kashmir Rechords has restored visibility to a man whom history had pushed into the margins. The archive does not embellish Jalla’s suffering; it simply allows his own words, scars and silences to speak again—decades later, to a generation that never knew such a spy existed.

After the mass exodus of Kashmiri Pandits, Jalla drifted away from the Valley he had once served so fiercely. According to Ravinder Pandita, President of the All India Kashmiri Samaj and a fellow Rainawarian, Jalla spent his final years somewhere near Bhimtal, battling illness, obscurity and disillusionment. In August 2021, he died quietly—without recognition, without closure.

Kashmir Rechords, by preserving and reproducing some portion of this rare issue of The Illustrated Weekly of India, does more than archive history—it restores dignity to a man the Nation then forgot.

If Bollywood celebrates fictional spies, Roshan Lal Jalla reminds us of the cost borne by real ones—men who returned not to applause, but to abandonment.

Some heroes don’t die on the battlefield.

They die waiting to be remembered. And sometimes, remembering them is the least a Nation can do.

=====