WHEN THE WHITE COAT TURNS GREY

(Kashmir Rechords Archival Desk)

The recent arrests of Kashmiri-origin doctors in the Red Fort blast conspiracy—stretching from Faridabad and Lucknow to Pathankot and Srinagar—have once again exposed a troubling undercurrent in Kashmir’s conflict narrative: the ease with which some medical professionals have drifted, been dragged, or been willingly drawn into the orbit of militancy.

Even militants themselves have often prefixed their nom de guerre with “Doctor”—not because they possessed a degree, but because the title carried credibility, trust and influence in Kashmiri society.

This pattern is not new. It has a trail more than three decades long, full of contradictions—doctors who healed the injured by day and ideologised insurgents by night; doctors who acted as mediators between the government and militants; doctors who protected militants, treated them secretly in hospital wards; and doctors who were themselves kidnapped, shot dead, or punished for defying militant diktats.

The 2025 case is only the latest reminder.

A History Written in Hospital Corridors

From the very beginning of militancy in 1989, medical institutions—particularly SKIMS, SMHS and Bone & Joint Hospital—became shadow theatres of insurgency. Militants sought treatment there covertly; sympathetic staff helped them; and those who resisted often paid with their lives.

The medical fraternity enjoyed unparalleled respect, which is precisely why militants found it useful to infiltrate or influence it.

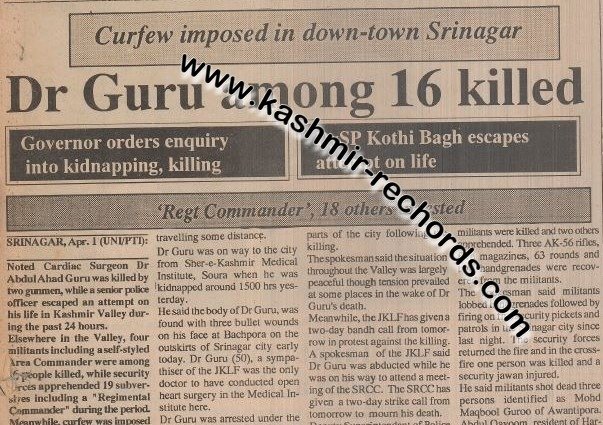

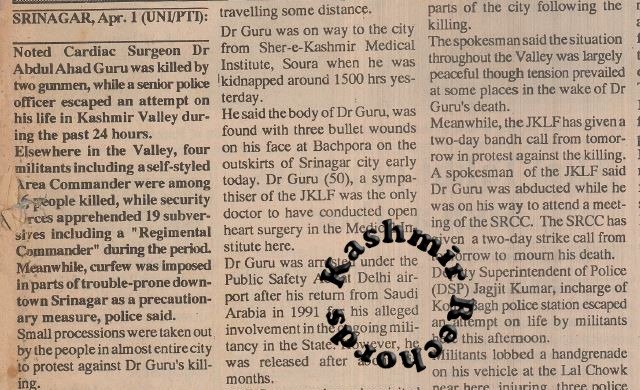

No figure symbolises this complex overlap more sharply than Dr Abdul Ahad Guru, the famed cardiac surgeon who performed the first open-heart surgery at SKIMS. Revered professionally, he also became literary “Dr Guru,” the ideological guide of the banned Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF).

This was not a title invented by militants—he was genuinely a doctor and a respected public intellectual who, in the first phase of the insurgency, enjoyed extraordinary influence.

He visited Saudi Arabia in 1991; he was detained multiple times under the Public Safety Act; he was released under public pressure.

But on 31 March 1993, he was abducted by the very gunmen whom he supported. His body was found the next day, triggering valley-wide protests and a bandh openly announced by JKLF.

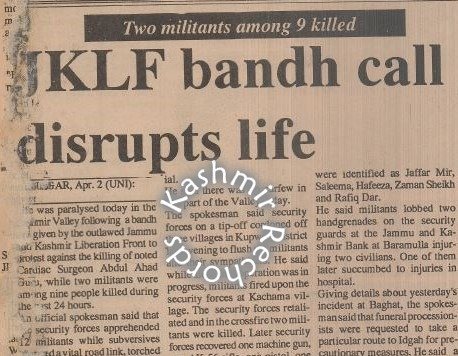

His killing remains one of the most politically charged assassinations of that early insurgent era, with JKLF giving a call for entire Kashmir shut-down, triggering panic, disrupting life and forcing authorities to clamp curfew.

That same period saw a series of doctor-related tragedies, many of them documented by Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, and contemporary newspapers.

Doctors as Victims, Doctors as Suspects

Dr Farooq Ahmad Ashai, known for his criticism of alleged human-rights violations, was shot dead on 18 February 1993. Human Rights Watch recorded that he was shot while travelling in a car marked with a red cross. Local rumours painted him as a militant sympathiser—illustrating how lives fell between official suspicion and militant coercion.

Sarla Bhat, a young nurse at SKIMS, was kidnapped from her hostel and murdered on 18 April 1990—one of the earliest militant actions aimed at intimidating Kashmiri Pandit medical staff and asserting control over the Institute, which at that time was crawling with militant activity.

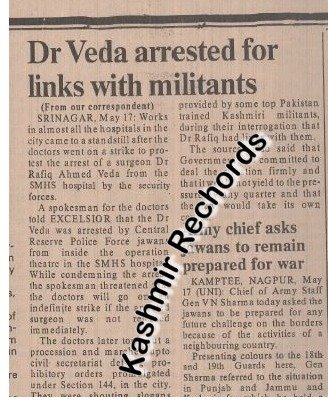

Dr Rafiq Ahmad Veda, a senior doctor at SMHS Hospital, was arrested on 17 May 1990 for alleged links with Pakistani handlers. His arrest provoked an unprecedented doctors’ strike that paralysed Srinagar’s healthcare system.

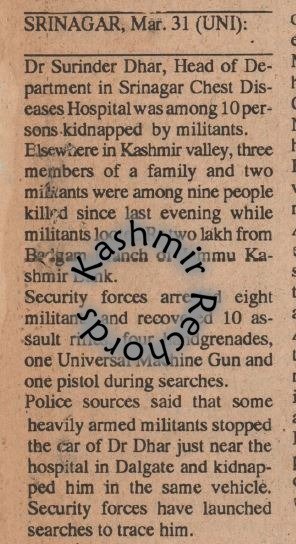

Dr Surinder Dhar, Head of Chest Diseases Hospital, was abducted on 31 March 1992 after he refused to treat an injured militant without notifying the police.

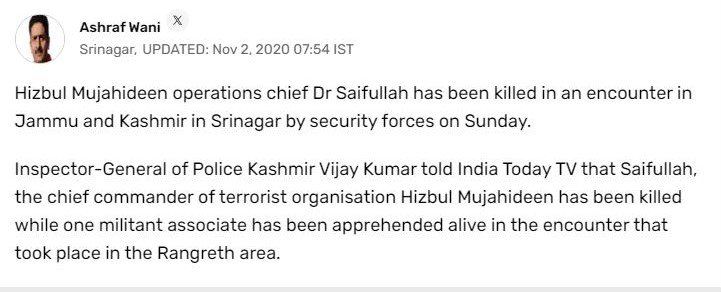

At the same time, militants began adopting “Doctor” as a battlefield alias because of the inherent weight the title carried. Saifullah Mir, widely known as “Doctor Saif”, though not medically trained, was one such Hizbul Mujahideen commander who supposedly tended to wounded militants.

For militants, the prefix wasn’t academic—it was psychological warfare.

The New Face of an Old Pattern: Red Fort Blast Case

The terror module busted in November 2025 shows that the doctor-militancy nexus has not vanished; it has merely transformed its methods—from covert medical help in hospitals to online radicalisation, inter-state movement, encrypted communication and operational roles.

Among those arrested or implicated in the Red Fort blast investigation:

• Dr Shaheena Shahid, a medical practitioner with an academic background, accused of being a recruiter linked to Jaish-e-Mohammed’s women’s wing (allegations under investigation).

• Dr Umar-un-Nabi, a Kashmiri doctor whom investigators suspect was connected to the explosive-laden Hyundai i20 that blew up near Red Fort on 10 November 2025.

• Dr Adeel Majeed Rather and Dr Muzammil Shakeel, whose arrests widened the probe across multiple states.

The profession is again facing uncomfortable scrutiny—because the symbolism of a white coat offers both camouflage and credibility to militant networks.

Why Doctors? The Inconvenient Truth

Three threads have remained constant across the decades:

- Credibility: Doctors command trust. A radicalised or compromised doctor can move unnoticed across checkpoints, social circles and institutions.

- Access: Hospitals, especially during the 1990s, were safe spaces for militants seeking treatment, refuge or contact.

- Influence: A doctor’s word in Kashmiri society carries weight—making them ideal mediators, facilitators or ideological influencers.

It is this mix of access, respect and authority that made doctors valuable to militant groups then—and continues to do so now.

The White Coat, Once Again in Question

The re-emergence of doctors in terror-related investigations unsettles public faith, not just in the profession but in the fragile relationship between medicine and conflict in Kashmir.

From Dr Guru to the SKIMS kidnappings, from “Doctor Saif” to the Red Fort blast module, the story has been one of a profession repeatedly pulled into the grey zones of insurgency—sometimes willingly, sometimes under threat, and sometimes fatally.

The 2025 arrests are not an entirely new chapter—they are a continuation of a long, complicated, and deeply troubling story.

When the conflict reaches the corridors of medicine, a society loses not only healers—it loses its last refuge of neutrality.